Birds in Flight

On Christmas afternoon, I lost the family pet. We had friends visiting from America and had just returned from a walk in the park together; I was straightening, readying ingredients, resolving arguments, with a yellow bird on my head. Our cockatiel Charlie often perches there, it gives her some height and distance from the chaos of my kids, a lifting off point for flight around our house. When I slid the glass doors open and stepped out into the garden with a child’s muddy scooter, I forgot she was with me. And when I threw the scooter into the shed, the jerk of my arm, the sound of the clatter, they happened so in tandem I don’t know which, scared her. And I felt my mistake before I saw it: lift off.

Bewildered, I watched her fly over the gardens of our neighbors, farther and farther, heard her panicked call and then it and she were gone, subsumed by the traffic and other bird calls. And finally I called for her, throwing my voice to her, a hopeful net, a futile reach.

My husband heard my alarm first. When he learned what had happened, I could feel his unspoken frustration and anger. I am clumsy with things, and sometimes people, too.

As the two of us and our four kids were combing the neighborhood, my six-year-old Nicholas asked, “would it be worse to lose me or lose Charlie—I mean who would you miss more?” And of course I had considered that calculation almost immediately: thank god it’s the bird, not a child.

Loss reminds me of loss. The loss of a pet foreshadowing more serious losses, a simulacrum of that feeling of disbelief, that I could have something or someone and then nothing or no one so quickly. A bird on the head, a bird in the air, open sky, then nothing. Pet loss so often comes from a careless choice or a lazy choice. But so does person loss.

When my youngest son fell off my shoulders he was only just over a year old. I was alone on a French hillside where we’d spent the afternoon exploring ruins. My husband had run ahead to get the car, my mother had taken my two eldest, and my father had gone down with the bags. I was left with the two youngest, each refusing to walk any farther. I’d hoisted Evander on my shoulders, then reached to pick up Nicholas, and, as I straightened up, I took my arm off Evander’s leg to stop Nicholas from slipping.

As Evander spun down, I spun around to see him, face down and still on the ground. He was dead. He looked dead. I thought he was dead. I couldn’t speak, but I scrabbled at his body, and rolled him over. His eyes were wide open, and his face was saturated in blood. Too much to make sense of the source of it. I shrieked, the loudest I’ve ever shrieked, loud enough for whoever was near and far to hear. I held him up and his blood was a torrent, his body sliding in my wet hands.

By the time we found a hospital in the French countryside, my hair, neck, shirt, pants were caked in his rusty blood. They refused to use anesthesia for babies, so my mother and I had to hold him down as they made the nine stitches inside and outside his mouth. I watched his body writhe in pain and then passed out on top of him halfway through his operation. A doctor wheeled me out in the hall where I was forced to remain lying down, listening to his screams. He’ll bear the facial scar for life; I’ll bear the memory for life.

Directly after each event— the baby on the shoulders, the bird on the head—my memory suggested there was a breath of a second when I’d had a choice, a split second awareness of the dangers inherent. Like time’s version of the Pauli exclusion principle of two things never touching, within that space I’d had a moment when I considered not doing what I was about to do. I don’t know if this awareness is retrospective, but in the immediate memory of the event, it felt like I had gambled, like I wanted to see how the universe would respond to my risk. Like I had placed bets with lives.

These accidents always seem to be on the backs of banner days: the first half is magical and then tragedy ensues, as if the world is righting a happiness ratio. We spent the final hour of daylight on Christmas looking for Charlie, calling and whistling up and down the street, the children’s grief like dominos: by the time the keening got to my youngest, it was hard to distinguish real feeling from histrionics. No one had an appetite for Christmas dinner, and Nicholas got a migraine. In lieu of dessert, he and I sat in the dark on the floor of the bathroom as he shrieked in pain asking for it to stop, reminding me not to say it’s going to be okay: “it’s not okay!” Instead I whispered again and again, “I am here, I am with you, I am here” and it felt like atonement, the beginning of ablution for losing his pet, for ruining Christmas.

We canceled our plans to travel with our visiting friends the next day, and instead hunted for Charlie. My husband went on his own, up through the nearest urban center, the direction I thought I saw her fly. I took the kids to the park across the street; we walked and played a cockatiel flock call on YouTube, my second son marching ahead in his high tops with the speaker on his head like a young John Cusack in Say Anything, pleading for his girl to emerge.

In a pine tree across the field, I thought I saw a glint of yellow. We ran to it, until I realized it had been a trick of the sun on a pinecone. My oldest stood in the needles, under those tall trees, silently crying. He’s almost a teenager but it’s hard for me not to see the infant in his running nose. And I wondered at the chances of finding one specific bird. Is it fair to build a narrative of hope I no longer believe in?

My last gross miscalculation with a pet was in third grade: Teddy, a hamster that my brother, a friend and I were playing hide-and-seek with in the backyard. A crow swooped down to the plant where one of us had just hidden Teddy, and I watched in horror as the crow flapped off, my new pet wriggling in its talons.

Losing a pet as a child is devastating; losing a pet as a parent is juggling three swords: your kids’ emotions (balancing the importance of crying and the need for distraction); your own emotions; your understanding of the hard world your pampered pet has just entered and their likely pain because of it, then modifying that narrative for your children.

Right after Charlie flew away, in my initial disbelief, I’d said too much to my eldest, mentioned how unlikely it seemed to me that a bird, bred in captivity, could make it, with the cold, the foxes, the crows, outdoor cats looking for murder.

Cockatiels are ground feeders, but we knew she’d be panicked and more likely perched, so we looked up, all of us, a band of five calling her name, whistling, singing, looking for yellow. Many birds were easy to dismiss, for color, for size, but they caught my attention anyway. I’ve developed a mild interest in birds, because I’m over forty. Pigeons hunched everywhere like fat detectives; magpies in their love pairs, crackling to each other like dried noses; seagulls elbowing through the sky up from the Thames; coal tits chittering in their silly black war helmets, protecting their hedges at all costs. The sinister luxury of a crow flap. The gang of ring-necked parakeets, their tail feathers like green knives in the sky.

Once I asked my oldest son, who was taking a digital art class, to make me a photo of a branch of these green bullies in Santa hats. The only naturalized parrot in the UK, they’re a shock to see in London for the first time: like green travelers from a faraway land. But they’re immigrants like us, their origin unclear but full of legend. The most common theory is they were pets released in the mid-twentieth century when a nation-wide fad of parrot import was followed by a nation-wide fear of parrot fever. Household pets were released to fend for themselves in a radically new climate.

You have to respect them, these parrots transported across the globe, who not only made it but thrived. The last official roost count, in 2012, recorded 32,000 parakeets in London, but in the decade we’ve lived here, their populations have swollen. We used to have to go south of the river to see flocks of them, now they’re everywhere: on our walk to school, in all our local parks, in our back garden bullying out the other birds, even the squirrels, at the feeder.

They’re talking parrots, known for being able to learn long sentences, and every now and then, you’ll get an inane phrase from a tree or the sky.

As a child, my recurring dreams always had to do with flying. Sometimes falling, sometimes lifting off, but always in some kind of bodily flight. When I was five, I visited a neighbor who had a side-hustle as a birthday clown, to ask her to teach me the magic for flying. In middle age, this interest in flying has returned, and tempered by reality and science, it’s transformed into an interest in birds.

Crows are the brilliant minds but lutino cockatiels are the golden retrievers of the bird world: they’re friendly, attached to people, have a yellow crest like a punk mohawk but rosy cheeks like a child who’s gotten into its mother’s make up drawer. They are delightfully absurd and usually attach themselves to one person. In our case, it’s my husband. He can whistle to her and she’ll come, hawk-like to hand.

The closest my husband has gotten to leaving me was when we got our bird. Before I brought Charlie home, I’d been researching birds for a while, and had settled on the cockatiel. At the end of the school year, one showed up, on the head of a student, in a yearbook spread about students and their pets. When I asked her about cockatiels as pets, she revealed her mother was insistent she get rid of her bird when she went to college the following year. Enter us. For over a year, I conferred with this student and her mother about adopting their cockatiel.

Except I never consulted my husband because during that time he was with his dying father. I picked Charlie the cockatiel up four days after my father-in-law’s memorial service.

My husband likes order, cleanliness. Had we the money and time, I’d like the chaos of a menagerie. I meet his minimalism with my maximalism. He has a keen sense of hearing, and I’ve never heard well: a bird’s squawks and shrieks are little addition to the swells of four boys in a house, for me. Charlie chirps when we come home or leave the house, like a dog. And after we all left the house each morning, only my work-from-home husband and Charlie remained. Resistant roommates.

And then, a week in, she became his companion, a being to sit with in his lonely grief. He insists now that she be out of her cage, free, flying around our house all day, even as he’s scrubbing bird shit from the baseboards.

There are two ways people rescue pet cockatiels: you see where they alight and coax them down after their fear subsides, or someone must find them on the last day of their survival when they’re so depleted they seek out strangers and don’t fly, they find someone willing to help before a predator gets them.

In the days after losing Charlie, between Christmas and New Years, I joined eight online bird groups, hoping someone would report a sighting of her. People shared, my post but also their stories. An African grey parrot, also named Charlie, disappeared for three months, and just as his family gave up hope, he was found, miles from home. I became deeply invested in the story of another missing pair of cockatiels who flew away the same day as Charlie. One woman online updated me each time she went out looking for our bird.

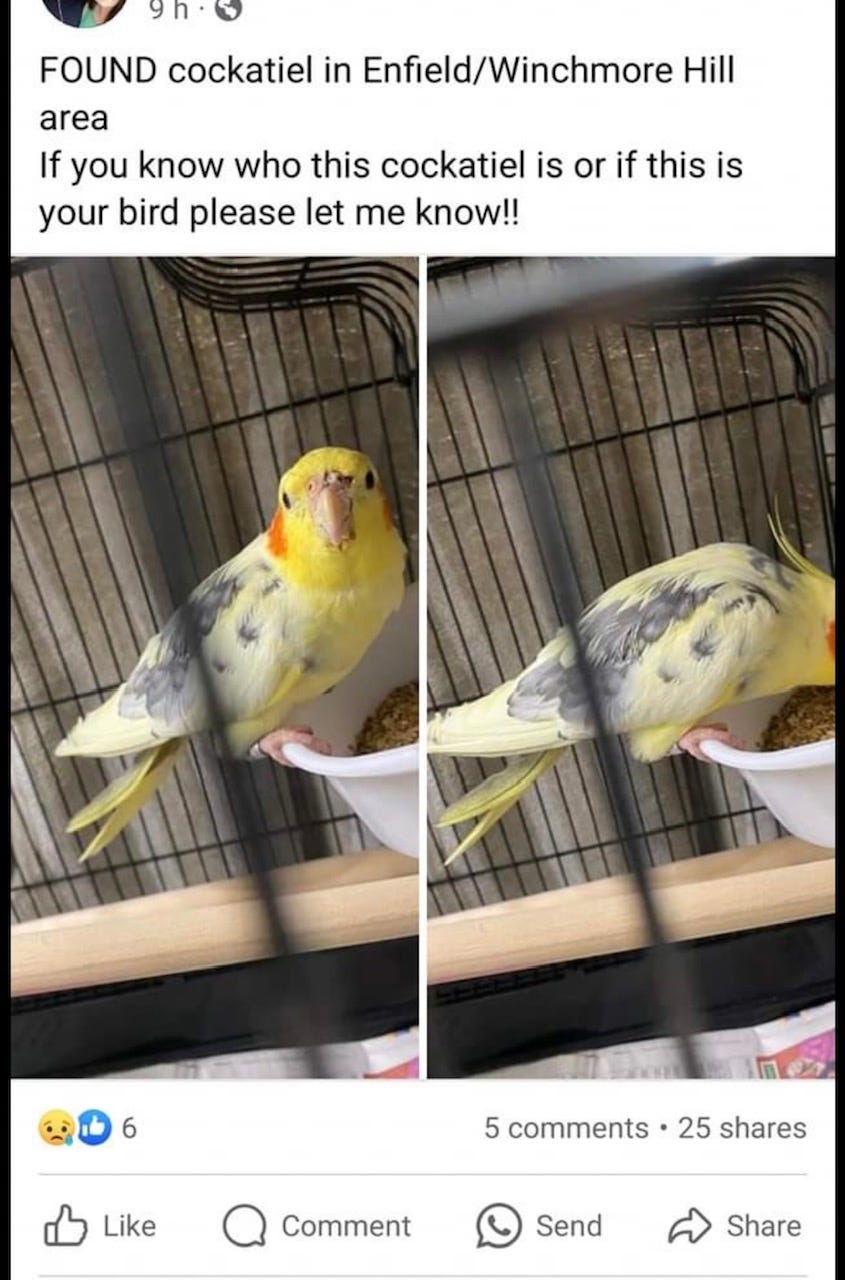

On the fourth day of Christmas—the day of calling birds—we got a ding. Someone forwarded a vet office’s post to me. The vet was in Enfield, 11 miles north of us. Unlikely, but the grey markings on the bird’s feathers in the photo looked identical to Charlie’s. This bird had been found wandering the parking lot of a Waitrose grocery store, looking exhausted and unable to fly.

We got up early and drove to Enfield to see if that bird was our bird, holding our breath as we passed over the north circular highway, wondering how a bird in captivity would make it that far, where she might alight on her way. What a wild thing a bird is.

The moment they brought the cage in, it was clear. She paced her bar, chirping. Half her tail feathers had been bitten off, her face scratched, but she whistled back a few bars of The Addams Family theme song to my husband and made a juddering flight directly to his chest. And then, to my relief, my head.

She’s lucky, the vet said. The fact that she flies free in our house meant stronger wings, better survival instincts.

These stories of delivering a lost pet home to one’s children are rare, I know. And I am filled with relief. But also, when we go out, and I instinctively look to the trees to watch for flashes of yellow even as I know ours has already been found, I’m reminded that there’s something wonderful about looking up. There’s something wonderful about seeing something go free and wondering at its journey.

My husband said I looked stunned, standing out in the back garden after Charlie left. And it’s true, I was full of wonder as I watched my bird lift off, fly higher than she’d ever flown, despite so many certain dangers; to watch her not look back, up and up and up.

Thank you to the marvelous trio, Meryl Rowlands Diana Demco Becky Isjwara, for the thoughtful feedback on this essay. A few days before Charlie flew away, a friend told me the story of finding an injured hedgehog on the side of the road. She insisted she and her mother take the hedgehog to a vet, 45 minutes away. As we were looking for Charlie, I thought about that story, that friend, how much I hoped Charlie would find someone like her when she was ready to come down from the sky. Thank you to the anonymous person who stopped in the midst of their grocery shopping and whatever else they had going that day to rescue our bird.

You and your bird(s) and your words 💖

Epic story and so well told 🙏🏻