Break up's Spell

the creative catapult born of heartbreak and some artists for this day

In mid-February 2003, people in 600 cities worldwide protested the invasion of Iraq, NASA was still making sense of the Space Shuttle Columbia explosion, Dolly the cloned sheep was euthanized because of lung disease, and the man I thought I might marry broke up with me.

My friends convinced me to come to a party on Valentine’s night to distract myself from my grief and to give themselves a break from my obsessive dialogue. But most distractions from heartbreak end up just pushing further on the bruise: couples you thought would never make it, offering you condolences; reminders of him in clothes, on walls, in drinks; the general joy in others.

Around midnight, I left to walk home alone, both boots on, the anti-Cinderella. It was cold, sleeting when I crossed the Duke Ellington Memorial Bridge from Adams Morgan to Woodley Park. In the daytime, you can hear the zoo animals’ calls drifting up, but on this night it was the shush of tires on wet concrete and my sniffling.

I was just shy of 25 and hopeful that the headlights caught my tears. The biting cold felt strangely like romance itself, and I wanted to share my sadness with strangers. Which, I think, is the first step out of heartbreak. And the best part of heartbreak.

Biological anthropologist Helen Fisher talks about two stages of heartbreak: the protest stage and the resignation stage. The protest stage is filled with drama, obsession, strategizing, trying to see what went wrong and trying to win the lover back, get back to status quo. This is when embarrassing texts, phone calls, stalking the ex’s haunts happen. This is where I called up all our mutual friends who were women in order for them to align with me, not my ex, for fear he might date one of them. (Later that year one of them became my new housemate, being safely ensconced under the same roof, where I knew betrayal couldn’t happen, brought me machiavellian relief.)

During the protest stage, our dopamine and norepinephrine receptors fire unremittingly in the brain and we allow ourselves to participate in thoughts and actions that pre-breakup would’ve made us ashamed. We are at once electrified and obsessed. Shame goes out the door as do the acceptable ways of being.

This is where creativity can be born.

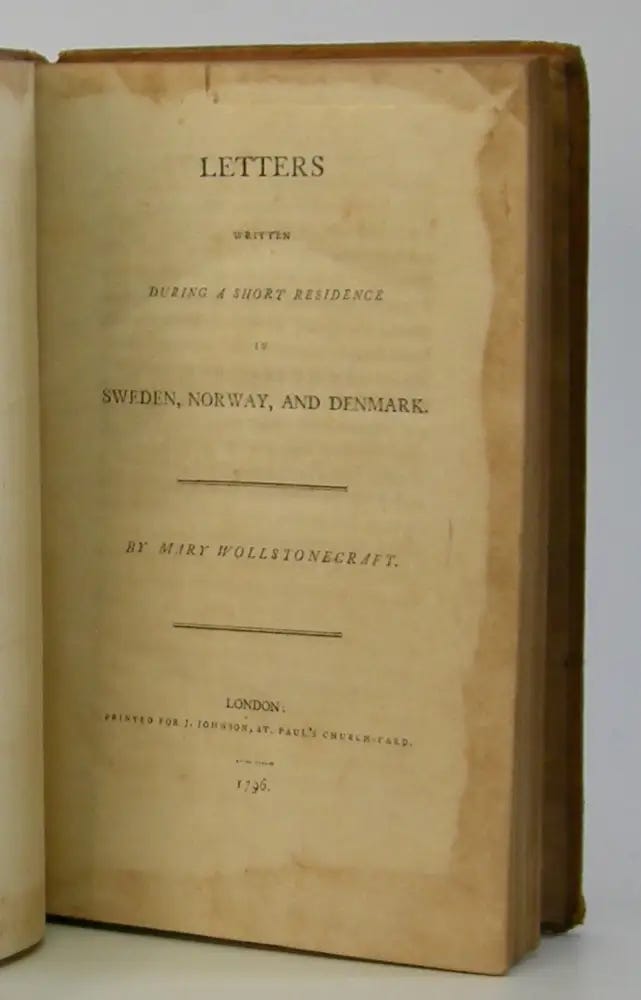

The travel memoir as we know it today was born out of this phase of heartbreak. Despite the cautions of friends and family, Mary Wollstonecraft traveled to Paris during the French Revolution. She wrote, observed, and fell in love with American adventurer and diplomatic representative Gilbert Imlay. He cared enough to get her pregnant, but after their child was born, he left Mary for an actress. Wollstonecraft was desperate to win him back, and jumped at an outlandish opportunity to do so.

Pursuing his business interests while attempting diplomacy, Gilbert had purchased trunks of French silver when prices plummeted in the revolution. But the ship of silver sent back to America had been pirated and last seen headed to Scandinavian waters.

And so, Mary, with her newborn and her postpartum depression, set off to Scandinavia on a treasure hunt to find Gilbert’s family flatware.

She never recovered the silver—it was a wild goose hunt of course—but the treasure she returned with was the world’s first travel divorce memoir: a series of letters chronicling customs, landscape, and desperate desire published as Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. It was groundbreaking for her day and ultimately led her to her husband and a man much more her intellectual equal: William Godwin. About her book, Godwin wrote: "If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book."

It was a book of beauty, not just for its depiction of the external snowy wilderness, but for its depiction of the internal swells of desire, and shameful desperation.

Another artist well acquainted with heartbreak, Sylvia Plath wrote in her poem “Jilted”:

Tonight the caustic wind, love,

Gossips late and soon,

And I wear the wry-faced pucker of

The sour lemon moon.

Is this a direct address to a beloved or is “love” the caustic wind? Her words are slippery, like our feelings in the midst of heartbreak. And in their slipperiness, their lack of concreteness, they become unrigid and full of possibility as they form themselves anew.

When we are jilted, the familiar is ripped out, and new ways of seeing force themselves upon us. And there’s a recklessness for creative minds, a nothing-to-lose quality that denies the restraints once asked of them. We talk about breaking down the walls of heartache, but sometimes heartache is the thing that breaks down the walls, the calcified rituals and expectations we place on ourselves.

In the days following Valentine's Day, I signed up for hip hop classes, enrolled in a free Italian program I’d found advertised on the Metro, attended a drawing class with my mother, and volunteered at Studio Theatre for free improv workshops. I was desperate to fill time and attention, but also to express what felt inexpressible with my tools at hand.

The comfort of a relationship creates a certain amount of inertia. In contentment, in comfort, there may be a desire to change or adapt, but there’s rarely a need.

Heartbreak lends itself to need. And need bears fruit once unconceived.

Sharon Olds’ husband left her after 30 years of marriage. A confessional poet, she promised her children she wouldn’t publish any poetry about it for at least a decade. 12 years later, out came Stags Leap. That collection, primal in its depiction of heartbreak and needs and including—not to be too punny—some of the world’s most staggering metaphors, won her the TS Eliot and the Pulitzer Prizes that year.

Perhaps a better word for the post-resignation phase of heartbreak, is heartcrack. Leonard Cohen sings in “Anthem”:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That's how the light gets in

Ejected from the den of the loved, I saw all kinds of things I’d missed, hidden in shadows in my relationship passivity. And in a world suddenly bright and abrasive, I realized I had to change to prevail. I wallowed and then filled my nights: besides the classes and workshops, I learned to speed read because I couldn’t process anything at the lingering pace I normally read— at the end of every paragraph, I was in a memory of him, an obsessive wondering of who he might date next, or an excoriation of myself.

Today, I am a lackluster drawer and a mediocre dancer and remember five phrases in Italian, but the will to jump out of myself did slowly, painstakingly bring me to a new path and so a new self, reassembled from that time of break. I left my job at an online travel magazine that was going nowhere (none of Mary Wollstonecraft’s lessons in vulnerability were allowed in the copy I was writing of gear reviews and hikes), and entered one of the world’s most vulnerable places: the writing classroom.

In “Pain I Did Not” from Stag’s Leap, Olds recounts what she felt she had to do in the aftermath of her husband’s leaving:

I think he had come, in private, to

feel he was dying, with me, and if

he had what it took to rip his way out, with his

teeth, then he could be born. And so he went

into another world – this

world, where I do not see or hear him –

and my job is to eat the whole car

of my anger, part by part, some parts

ground down to steel-dust.

In heartbreak, we eat cars we’d never need to eat from the comfort of a lover’s embrace. We find ourselves in freefall, yes, but also with a fleet of Ford Galaxies inside our belly. And there is a strange kind of nourishment in eating the engine. Even without our consent, it can drive us to create newness.

The final line of Olds’ collection is perhaps the most simple and the most generous in heartbreak history: “I freed him, he freed me.”

Happy Valentine’s to all the heartbroken. Make new, my friends.

A thank you to my friend, Eve Ellis, who introduced me to Stag’s Leap and so much more. Eve’s debut pamphlet is out soon, and I hope many of you get to relish in her beauty and brilliance.

First, there's the brilliant interplay between your personal experience and the work of a vast array of thinkers like Helen Fisher, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Sharon Olds (and a brief nod to Agatha Christie, too!). Nobody has ever written an essay that includes the work of those figures. You do this dazzling, deft weaving better than almost anyone I've read. It's one of your many gifts, and it's on full display here.

But what I especially admire about this essay is the way you invert our assumptions about the subject. The break-up not as pure devastation but as the seedbed for reinvention and creative possibility. It reminds of this chapter in Annie Dillard's An American Childhood (which I just reread and which I cannot overpraise) which begins: "Young children have no sense of wonder." You begin by saying, "What!?" and conclude by saying, "Now I see."