House of Hormones

An adolescent boy and a perimenopausal woman make strange housemates. Sometimes we’re in a quick-draw duel: Wild Bill Hickock meeting Davis Tutt, the dining room table between us our town square. I’ve got the experience and finances ready at my hip but he has the youthful energy and righteous indignation cocked in his holster. It’s rarely a fair fight: ultimately, I have the judicial power of consequences. And what does Gus have? The watery nature of my parental guilt or my steady forgetting of words, while he can explain the new dimensions of “demure” to me?

But we see each other so clearly, he and I, recognize the emotional extremes unwarranted by circumstance more than any of our other housemates. Last month, I bought a blanket for a friend as a housewarming gift. It was in our trunk, and while we were driving home, one of my other kids pulled it out of its packaging and wrapped himself up in it. Finding him thus cocooned, I was enraged, immediately catastrophizing: seeing in one incident an example of everything. They take and destroy everything I care about! I can’t even be a generous friend! The cocooner was shocked, if indignant. But not his older brother: “Mom, isn’t this kind of an overreaction?” Gus asked sincerely as I lurched from the car into the house, unspooling blanket under my arm.

My youngest child was born just a week shy of my 41st birthday. I stopped nursing when I turned 43 and didn’t realize for some time that I’d gone almost immediately into perimenopause. The first change I can point to was driving on the highway at dusk two years ago. I panicked. All my children were in the backseat, and I couldn’t read the signs ahead of me. My vision had gone completely fuzzy. When I saw an optometrist later that week, he said my eyes were fine, no change to my vision, must be in my head. As insulting as it is to hear “it’s in your head” from a medical professional, it turns out he was right. It was in my head: production of rhodopsin, the retina pigment that helps with night vision, drops significantly with perimenopause.

When I finally did figure out what was going on with me, it all felt terrifically unfair. After a decade of pregnancy, birth, and nursing, to be at odds again with my body: I thought we’d have some time, she and I, to just be. Puberty also feels grossly unfair, partly because it’s an embodied rebellion, partly because no one on the outside fully appreciates the upheaval an adolescent is contending with on the inside. One of the fears I had in adolescence and now in menopause is that the body—my body—-doesn’t fit the landscape: there is something monumental brewing on the inside and it’s impossible that life as we know it—city, school, neighborhood, living room—can contain it.

Outside the home, a body must constantly oblige its surroundings (stay upright, keep your distance, cover your mouth, get your finger out of your nose), but when you’re feeling windswept by hormonal changes, carved out like a cave, it’s hard to meet those obligations. Gus’s sleep patterns don’t meet the demands of middle school; mine don’t meet the demands of modern civilization. He’s reading until midnight, and forced up before the sun. I’m asleep by 10 then awake with a night sweat, and spinning from 2AM until my alarm. We’re both exhausted and often close to screaming (me) or shutting down (him).

While his hypothalamus is gleefully producing testosterone, my estrogen is too low to respond to my hypothalamus’s demands. When you’re low on estrogen, the hypothalamus sends increasingly frantic signals (LH and FSH) to get the ovaries to release eggs. But when the eggs are in shorter supply, the brain’s messages have little effect. And when it goes unanswered, the brain goes a little nuts—like that obsessive ex whose calls you didn’t return.

Revenge gets ugly here. With estrogen not texting back, the brain can’t even figure out how to regulate body temperature. There is not a place in the human body untouched by sex hormones. Estrogen receptors are at every place in your body, which is why the bones, muscles, fat, senses, metabolism, memory, mind all take a hit. And why, at ANY point in the month, you can go from fine to extreme rage or despair or find yourself suddenly soaking wet. And forget the body’s sleep and wake cycles: perimenopausal women are part nocturnal, like barn owls. Depression, loss of executive function (ADHD-like symptoms), brain fog, severe fatigue—1 in 5 women will leave their jobs as a result of perimenopause.

For the last two years, I‘ve been nagging all the women who’ve been through it about this ride. Gathering anecdotes, details, advice. Many of them tell me the same facts, but I nod like it’s a revelation. I want them to keep talking.

While I’m rounding up women like a sheep dog, Gus and most adolescent boys are far more alone in their changes. (Not unlike my grandmother’s approach to menopause.) They don’t have a cadre of older boys to turn to as resources. Instead, they rely on cringey health classes and parents. Which means sleepy, ragey, or dopey, I need to be present and talking and—most of all—listening.

In her essay “The Blue of Distance”, Rebecca Solnit describes a family at the Grand Canyon, where the adults scan the vista, feeling the majesty in its vastness; but the children are crawling around in the dust, enthralled by pine cones, feathers, and sparkly sandstone. Standing at the same point, one is delighted by the small, the other is delighted by the big, neither quite understanding the other’s delight. Solnit explains that “the blue distance comes with time, with the discovery of melancholy, of loss, the texture of longing, of the complexity of the terrain we traverse, and with the years of travel.” If a child is lucky, their first major loss will be themselves—their child selves. When I walk up to Gus’s room on the third floor, I can see it in his hands, as he half-heartedly puts together and takes apart legos, trying to get back the excitement he once had connecting and dismantling small things. The slowness with which he retrieves another block from the bin, the gaze to some unseen spot in the room, the hunched shoulders, all speak of grief. He is grieving the end of his childhood.

I remember this feeling of trying to rekindle some joy I’d once had making houses for my dolls and stuffed animals. I thought if I could put my body through the motion of nestling two sets of folded socks together to make a couch for Barbie, I might find again the attention, contentment, and deep satisfaction. Instead, I was both bored and mourning.

The sudden blueness of adolescence is upon my eldest: a world beyond feathers and rocks that feels vast and alienating. I can see—I can feel—his disorientation from seeing things so close, to suddenly seeing things so far. And for me, coming out of caring for babies, where the immediate details dominate, where survival is contingent on parental myopia, and launching into hormonal upheaval, I, too, feel my current blue period is sudden and unexpected.

At the end of her essay, Solnit describes the perspective from an airplane: “From miles up in the sky, the land looks like a map of itself, but without any of the points of reference that make maps make sense.” Being on a plane is disorienting; it’s not how we were designed as a species—to see things aerially. Hormone crashes have felt, to me, like this same disorientation. It’s that moment of surreality on the plane when everyone around you is drinking from plastic wine bottles, watching movies or doing sudoku, and everything appears normal, but you’re at the window, forehead pressed against the cold plexiglass thinking “what the fuck? I’m in a tin can, jetting across a continent. I AM NOT A BIRD.”

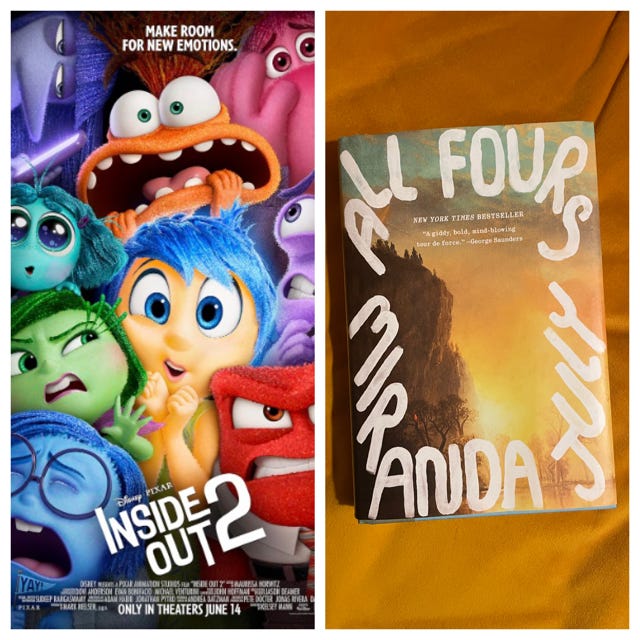

This summer, both Gus and I found some relief, some reflections on the outside of what was going on in the inside. Right after school let out in June, we went to see Inside Out 2. The emotions of childhood are kicked out of the main character Riley’s control center because the more complex emotions of adolescence have invaded. In their fight to get back to save Riley from her anxiety, standing at the base of a mountain of discarded memories, Disgust asks Joy: “So. What do we do now?” Joy looks down and says, “I don’t know…maybe this is what happens when you grow up, you feel less joy.” It’s the suckerpunch moment of the movie, for its truth, but also because we know it’s only a half-truth; there’s a turn coming. Riley needs to make it over this threshold of hormonal upheaval.

As we shuffled out of the theater, Gus wrapped his arms around my waist, put his head on my shoulder. My son saw himself, entirely, in the movie. And best of all: it’s a kid’s movie, so while it provides the mirror to those interior complexities, it’s not an insistence to give up childhood. And right now, childhood is something he doesn’t want to leave behind, not totally, not yet. Half of him is fighting back to it, upstream, like Joy, Sadness, Disgust, Fear, and Anger in Riley’s interior landscape.

But you can only cup the water of who you were for so long.

Late this summer, when he was reading about magical swords but also about what happened in Bosnia, I took Gus to California to visit his godparents. While we were hiking the redwoods, he explained to me a couple of his fears. Thinking about the size and expansion of the universe, he said, can bring him to tears some nights. And the question of what happens beyond metacognition makes him sweat. Puberty and menopause transcend the family dilemma at the Grand Canyon because the Grand Canyon is suddenly made small. We’re intergalactic, people.

On Sunday afternoons this autumn, Gus and I have felt even more despair than the usual Sunday dread. I think since our bodies are also in transition, the transitional day of the week—from weekend to weekdays, from home to school—feels like a double-assault. On the Sundays we can convince each other to do so, we’ve gone walking in the park across the street. This last decade, they’ve let the grasses go wild in many of London’s parks, and this park is situated on a hill, where, when the weather obliges, we get dramatic sunsets. Sometimes, the sky offers perspective to the small futilities and loss of self we each feel standing amidst the grasses. Not the disorienting perspective of looking down from a plane, but the reorienting perspective of looking up together, at the clouds. And at the deepening blue.

Besides the women in my life who’ve been through it/are going through it, a few of my favorite resources are here:

Zoe has done a ground-breaking food study on effects on menopause. Davina McCall talks about that and a fascinating cluster study about symptoms on this podcast. Her book Menopausing: The Positive Roadmap to Your Second Spring blends personal experience with research. (The UK is ahead of the US in menopause research and discussion, perhaps because they’ve had a few post-menopausal women in charge already.)

Dr. Mary Claire Haver talks the science and symptoms of menopause on Huberman Lab (I also recommend following her—she’s got a new book out, The New Menopause)

Eve by Cat Bohannon (menopause is a chapter, but this book looks at all aspects of female anatomy and explains why women’s bodies have not been studied, and why research for 50% of the human population is still like a black hole. Just to give you a sense of how new all this work is on something that’s been going on for millennia: “perimenopause” shows up here in Substack as a misspelling.)

And of course: All Fours by Miranda July, about what happens when we choose desire over obligation and so so so very much more. I loved this discussion between July and Esther Perel.

HRT (which deserves an essay of its own)

Puberty books have been around for a lot longer, but I did find this conversation between Ezra Klein and Richard Reeves (“The Men—and Boys—Are Not Alright”) really interesting as I approach the shifting landscape of masculinity with my students and my sons.

I’d love more suggestions for listening/reading/consuming: please drop them in the comments if you have them. The more knowledge, the more sharing, the easier this transition is.

💙 💙 💙 💙