Super Hag

and the quest for invisible wisdom

“Flight or invisibility?” asked The New York Times op-ed writer Jennifer Finney Boylan, surveying my students and me pressed around the table, on her 2019 visit to London.

“Flight,” I replied without thought. I was deeply pregnant with my fourth child, my body increasingly leaden and bound to the earth, an anchor becoming an anvil lodged. But I’ve always chosen the superpower of flight. There’s a loneliness to each superpower as there’s a loneliness to the superheroes that wield them, always living clandestinely, usually a double-life even loved ones don’t know or understand. Coming off as common-place, but performing necessary feats unbeknownst to all around them.

The loneliness of flight is a solitude—being above it all, seeing below, a fuller picture. The only company, the wind, the rush almost unbearable. But where flight speaks to solitude, invisibility speaks to deep loneliness—to be among and unseen, to be ignored, to be not even missed, because were you ever really there? Can something unseen have matter? Can it matter?

I’ve been thinking about the invisible lately because in a decade, maybe two, I won’t have flight, but I will have invisibility.

Friends, aunts, my mom, contestants on The Golden Bachelor have all said it: “I’m invisible.” There’s no self-pity in their tones, it’s just a statement of fact.

A very long-standing fact.

Akiko Busch describes the phenomenon as: “The invisible woman might be the actor no longer offered roles after her 40th birthday, the 50-year-old woman who can’t land a job interview, or the widow who finds her dinner invitations declining with the absence of her husband. She is the woman who finds that she is no longer the object of the male gaze—youth faded, childbearing years behind her, social value diminished.”

Are they really invisible? Some of my recent experiences point to yes, but am I complicit? For the last two weeks, I’ve been observing my own line of vision. I take the Tube to and from work every day, a feast for observation of the masses. Where do my eyes linger? What do my eyes avoid? I realize this study elides all steps of the scientific process. And yet, when I exit the train car, I have a harder time noting the details of older women. Without training myself to do so, I’m not paying much attention to them. Even as they present a snapshot of my future, I’m oblivious. I have made them irrelevant.

My mother was a model; she spent much time in the male gaze; I spent much of my childhood scowling at men gaping at my mother, and at the same time, looking at photos of her, wondering why I wasn’t as beautiful as she was. But my favorite photograph of her was taken recently. She is 73 in it, her cape thrown around her shoulders, her hand on her hip, her hair shining silver, her body looming large and dominating the horizon, as I sit on the beach below her and photograph her unawares. Her mouth is opening, in speech. As her estrogen has dwindled, since menopause and her hysterectomy, my mom has been franker. She is still loving, devoted, generous, but there is an honesty, too, in her words about what she needs. What she wants. And not everyone approves.

After gatherings with younger people, she and I have both discussed the way my peers’ eyes glide over her. I’ve watched her—this dynamic, extraordinary woman—go invisible to others before my eyes. A trick of light and age. She hasn’t opted for Botox, but she’s said she understands it as more than a desire for youth and beauty. Injecting snake venom also means prolonging your relevance in the world. A quick magic trick that helps in the moment but I fear sets us back further from where we must go if we’re going to celebrate women aging, benefit from what they have to teach us.

The British author Victoria Smith explores this diminishment in her book Hags: The Demonisation of Middle-Aged Women: “You are still an object; you’ve just changed in status from painting or sculpture, to say, hat stand.” Most of human history has not been fond of or kind to the older woman. A hat stand is comparatively gentle.

What the M-word tells us:

As the perimenopausal symptoms roll in—hot flashes, headaches, night sweats, distraction—I am just beginning to understand the effects of this invisibility. Everyone wants to talk about your pregnancy; no one wants to speak about your menopause. There’s a long tradition of saying by not saying this something that 50% of the population will experience. When my mother was starting perimenopause, she reached out to her elders. Knowing my grandmother’s sense of modesty, she waited until my grandma and her sister were together, and they’d each had a martini. Their response was shocking. Not because they refused to talk about it and their symptoms, but because these two sisters, self-proclaimed best friends, never more than an hour’s drive from each other all their lives, had never, ever talked about it with each other.

The condemnation of older women shows up in the scant medical knowledge we have of menopause. Scientists still don’t know the best way to treat menopause symptoms. “We know more about male baldness,” a friend reminded me the other night. What we do have are women who have been through it. 15% of our population at any one time knows something of it firsthand. We just need to see and hear them first.

At a reading last weekend at London’s Southbank Centre, a presenter walked out on stage in a fire-engine red jumpsuit. In her summary of the author’s new novel, she turned to the author: “I think this character is going through menopause, and as a 50-year-old woman, I’m really interested in this.”

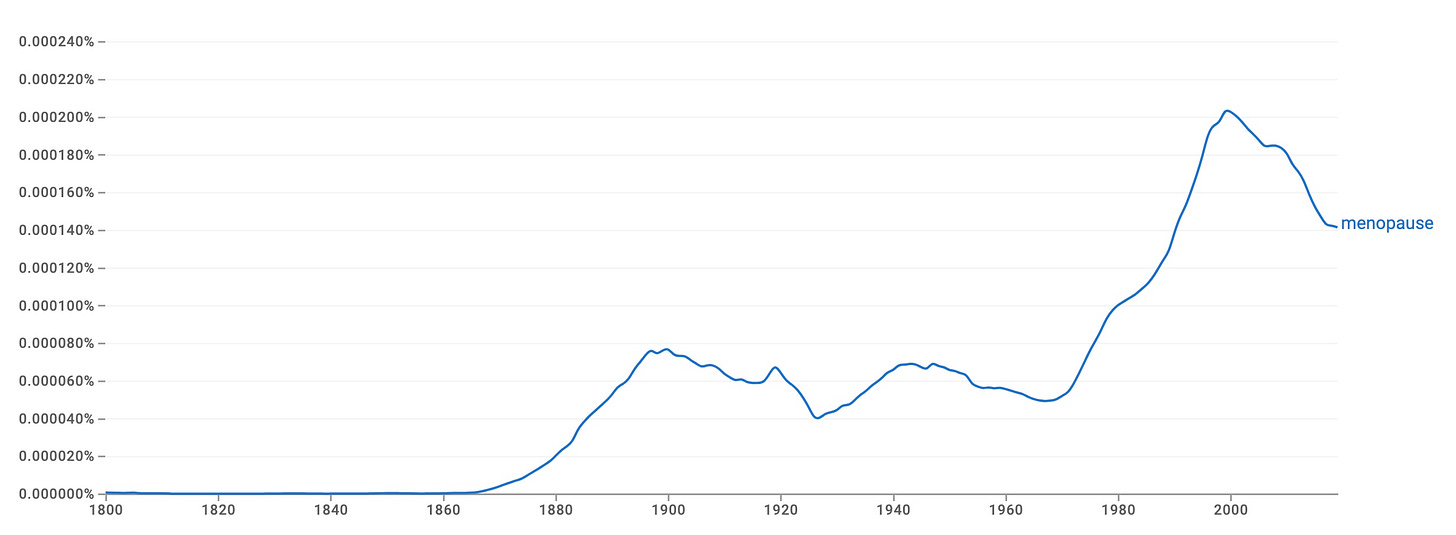

If you look at the frequency-of-use word chart, Google Ngram, “Menopause” rose in texts only as the boomer generation arrived to it, in 2000. Before that? Almost non-existent. And before 1852? Absolutely non-existent. It’s recent enough that to hear what was once invisible named on stage, gives a jolt.

How the Hag is born

The invisibility of older women springs from a number of sources. There are the artificial currencies of youth and beauty, of course, but the past has also shown us that a visible older woman has a target on her back. (We mothers, preoccupied by our children, are safest. Have always been deemed safest. The least likely disrupters.) Older women—especially unattached older women—have been pitied, but pity is almost always born of fear. And so, the pitiful old woman becomes the wicked old witch.

One needs only look at the statistics of the witch trials to understand the antipathy toward a woman in and beyond menopause (especially a woman who does not go gentle into that good night and disappear, especially a woman involved in medicine and healing with knowledge of the natural world). Two-thirds of those killed were women of menopausal age or older. Deemed, by their society, irrelevant. And somehow, paradoxically, in that irrelevancy: dangerous. The visible were made to disappear.

The lesson? For older women, silence and invisibility have long been a means to survival. This is ancient history, yes, but ancient history has a funny way of still stinking. We’ve all seen the legacy of those trials: the headlines about older women politicians, women in public spaces labeled “Hag”.

Like most self-involved people, I oftentimes become acutely aware of injustice only when it spills itself all over my shirt. It’s only because the invisible are women I’ve known since they were visible, only because I’ve hit perimenopause and the writing is on the wall for me, too, that I am recognizing my participation in this magic trick. Make the woman disappear!

The real magic

There is no body that changes more than a woman’s body. As we are talking about essential 21st-century skills like grit and resilience, this is something worth noting. Before her body has even stopped growing, a girl is cycling, shedding every 28 days. For the average woman, these changes will occur 450 times, and within that span, many—not all—will get pregnant and their bodies will withstand producing 45% more blood, swelling, aching, bulging, vomiting, leaking, forgetting, burning, to grow a new member of our species. And then, while a man slowly loses testosterone over a 20 year period, a woman will have all of that chemical shift compounded and so intensified within four years. Superhero stuff.

It’s time, I know, to travel to Hagdom.

All the women I work with have been listening to BBC’s podcast, Witch. Of these women: one has two black cats and is named Eve, another burns herbs, another went through menopause before 30, and another isn’t sure she ever wants to have children. So they all have a bit of the witch about them. (I have a long, pointy, crooked nose, sufficiently witch-like.)

I’m late to the seance, and only started listening to the podcast as they are finishing it. In investigating the history of the word witch and its implications, the podcast’s topics are dizzying: women’s health, how the change in land rights affected the witch trials, invisibility, paganism, catholicism, fairytales, our relationship with nature, and the overlap of science and magic. It’s brilliant and heroic. The writing, by India Rakusen, is exquisite.

Like the women killed for witchcraft, the old witches of story are always filled with knowledge and agency, and our stories have chosen to see danger in their knowledge and agency. We don’t know what to do with the ambiguity of a woman who has lost what we value most about womanhood: childbearing, care-taking, youthful appearance, docility, and then who simultaneously refuses invisibility. So we witchify. Make the witches examples of what not to be in old age.

Witch’s eighth episode, “Hag,” begins in Fife, where Macbeth ordered the slaughter of Macduff’s entire family because of the paranoia born of the witches’ warning. Macbeth’s withered witches foretell of his success and the ramifications of his too-much ambition. Had he heeded their advice, lives would’ve been saved. And while he is the tragic hero, they are the antagonists.

In Slavic culture, Baba Yaga lives in the forest on the outskirts of society, communing with wildlife and testing moral character in humans. She is old and indifferent to what people think of her. In some stories, she is ferocious and ugly, an eater of children; in other stories, she helps the hero or knight on his quest and then disappears again into the forest, or up into the sky in her mortar with pestle.

In West African tradition, Obayifo is a shape-shifter who flies by night, looking for prey. In Ashanti Twi, oba means "child" and yi means “to remove”, quite literally, “to remove a child”. It’s not a far leap to the demonization of a female body that won’t produce a child.

In Celtic tradition, we have Cailleach, Gaelic for “old hag”. She has shaped mountains, valleys, but is also a “storm hag” who brings about certain destruction. And cold weather. (Which we happen to need right now.)

Is it time to rebrand the old witch? Wicked did it with the young witch.

Witches, superheroes. They share capes, flight, knowledge the rest of society doesn’t see. It seems not so hard, just an act of reenvisioning, to make the old witch a superhero.

My mother’s generation demanded medical care and research, uttered the word “menopause” aloud in conversations behind closed doors, mine declares it on stage, naming the thing only alluded to on the page. As a society, we are acknowledging the long-held judgments, silences; the once invisible, the once decried are being written about as complex characters.

There’s an opportunity here, for women have only relatively recently been the written voice of their own history. The story of the old woman is in the process of a makeover. Early feminists like Virginia Woolf whiffed the potential, insisting that if a novel is to stay novel, the old woman in the corner of every drawing room of every page must be allowed her complexity. “[Mrs. Brown] is an old lady of unlimited capacity and infinite variety; capable of appearing in any place; wearing any dress; saying anything and doing heaven knows what. But the things she says and the things she does and her eyes and her nose and her speech and her silence have an overwhelming fascination, for she is, of course, the spirit we live by, life itself.”

Perhaps the fears around menopause are because of the magic in it, the metamorphosis a woman’s body, her very chemistry undergo. Sharon Blackie suggests a magic in post-menopausal women at the end of episode 8 of Witch,

“Folktales and fairytales help us reimagine ourselves [...] We need new ways of imagining what an older woman can be in this culture. That isn’t ridicule, that isn’t irrelevant, that isn’t silenced. Because let’s face it, we are fertile creatures for a relatively short amount of time and by the time menopause comes around, most of us, if we’re lucky, have got at least another 30 years to live. What are we going to do with it? And I see menopause as a kind of alchemical process in which everything that is superfluous is burnt away, and we are left with the core, with the essence of who we are.”

Imagine if we can look in the mirror and not see crows feet with dread but as a life filled with enjoyment, not see age spots with dread but as years out of doors, not see jowls but a mouth with stories to tell? To be inspired by women’s age? To be inspired by the incredible feat that is a woman’s body from babyhood through old age? It begins with valuing the voices of women several steps ahead of us. Treating them like they’re ahead of us, not behind us as Ruth Handler suggests at the end of Barbie. “We mothers stand still so that our daughters can look back and see how far they've come.”

No, no, no. Let them be ahead and visible to us. So that one day we might say—

Call us Hags, watch us fly.

Sincerest thanks this week to Karena de Souza, a couple steps ahead and so full of knowledge, I want to bask in her light. To Miche Priest and Henri James, who encouraged this essay and urged me to make the ending one to remember and who, most importantly, are a part of this endeavor to put women on stages, and use their own stories for a better future for all. To Nicolas Marescaux for taking a look at a really ugly first draft and appreciating what I was trying to do. To Chris Coffman, for reminding me to tell a story and not lose my place in it. To Hannah for writing me a found poem in a recent moment of fury over this; to Phoebe for always seeing the through line even when no one else can; to Eve for bringing into my life this podcast, constant literary gifts, her genius; to Natalie and Becky for the conversations about why women are fundamentally built for change. To the women a few steps ahead of me who have shown me how to be a woman and how to live. And to my mom, for all the advice and feedback, chatting with me on the phone as I distractedly shuttled a child to a sleepover, and then the next day as I sat in a hotel bar waiting for another child at a birthday party, where strangely the wall behind me was mirrored glass with Mrs. Dalloway’s opening pages etched into it; opening pages in which she alludes to menopause, without explicitly naming it, and a book that ends with a moment of utter joy as 52-year-old Clarissa looks across the street and into the window at an older woman wrapping up her day. It felt a bit like the late nights 30 years ago, when we’d pour over my handwritten pages making corrections. Then I’d read aloud, and you’d type all my words out on that IBM PS/1, mom, finding their coherence. Thank you.

STUNNING. In tears. Thank you for writing this and the beauty of it ALL. I will now go hug and thank my mum and every other wonderful wise hag in my life.

Alissa, I won't pretend to relate to menopause. Period (pun intended).

But I love to relate to you and your writing. These two passages made me smile - for different reasons:

"Like most self-involved people, I oftentimes become acutely aware of injustice only when it spills itself all over my shirt." - So vulnerable. So honest. So real for most. And such a pithy and unique description.

"And to my mom, for all the advice and feedback, chatting with me on the phone as I distractedly shuttled a child to a sleepover, and then the next day as I sat in a hotel bar waiting for another child at a birthday party, where strangely the wall behind me was mirrored glass with Mrs. Dalloway’s opening pages etched into it; opening pages in which she alludes to menopause, without explicitly naming it, and a book that ends with a moment of utter joy as 52-year-old Clarissa looks across the street and into the window at an older woman wrapping up her day." - So poignant. So real. So honoring of your mother.