A History of Violence in Color

there’s no place like home, except—

To readers: this essay looks at male violence, primarily male sexual violence. I’m in gratitude to the women of resolve who have allowed me to share a small part of their stories here. Any names used have been changed to protect identities.

If you know what to look for, you spot it everywhere. Like your favorite color, if you have one, is always the easiest to spot.

I watched The Wizard of Oz this week with my kids, but it might as well have been two different films, what they were looking at, and what I was looking for.

The film begins and ends in Kansas sepia, a nostalgic and claustrophobic complement to the film’s vibrant center in Oz, filmed in three-strip technicolor. Post-production took forever. The MGM production crew argued for a week just about which hue of yellow was right for the yellow brick road that would take Dorothy and friends to Oz to meet a phony hat-trick of a man behind a curtain who disappears near movie’s end in a balloon called “Omaha”.

The scenes that horrified me as a child are hokey now. It all is, really, until you look at the production’s underbelly, then it’s hard not to see all the brightly-lit horrors. Even in all of the Me Too movement’s revelations, the abuse allegations and lack of safety on Oz’s set are shocking.

There’s the scene when Judy Garland meets the Lion and, giggling at Bert Lahr’s performance, she was slapped by Victor Fleming, the director. (He did later feel guilty, and asked other cast members to punch him in punishment.) And all the scenes in which Margaret Hamilton, the Wicked Witch, actually caught on fire, suffering first- and third-degree burns on her hands and face. But Fleming demanded Hamilton play with the fire again and again, no matter the damage. Then we arrive at the infamous snow on poppies, meant to wake the four travelers, save them from the wicked spell. But it turns out the snow was asbestos.

And there’s the moments outside of filming, too. Louis B Mayer (the final M in MGM) groping 16-year-old Garland over and over after forcing her to pop amphetamines and barbiturates to stay awake and skinny.

And as I’m following Garland’s jaunty skip down the yellow brick road, I’m also following another yellow brick road through another Oz of sorts.

I. On the first hot day of this summer in London, I met girlfriends at one of the few taco joints in this city. We ordered margaritas. They arrived cold, salty, sweating. Electric yellow. On our second round, I was recounting the rage I’d felt taking over recently. I’ve known sadness in my body, but this rage is new. “Oh, I know rage,” said my friend across the table. I’ve known this friend for eight years; she’s so cool I was a little in love with her the first time we met. “I know rage. I know it too well.”

And yes, it sits on her like a jean jacket as she tells me about when her dad had early onset dementia and her mom was undergoing dialysis, my friend’s basketball coach took her under wing. He brought her home and raped her from age 13 to 16.

And then she tells us about how she seethed when a 16-year-old boy looked sidelong at her six-year-old daughter on the playground that morning. The rage always a hair- trigger away.

II. From a distance Agnes Martin’s 1963 “Friendship” glimmers, a lusty gold landscape. But up close, the artist’s movements reveal themselves, cross-hatched lines and secrets for the person willing to look close. In my early thirties, I painted a wall of an apartment the color of “Friendship”. When we moved out, my friend moved in, painted over the yellow wall immediately. “That color is doing no one any favors,” she said, and I took unnecessary offense.

I wouldn’t know for many years that that same year that same friend was brutally raped by a friend that came to visit her. She told me about it this past spring. He’d been disbarred, locked away at last, for another rape. The news story harpooned her, she was vibrating with it, victim again, but also perpetrator for not reporting him a decade ago.

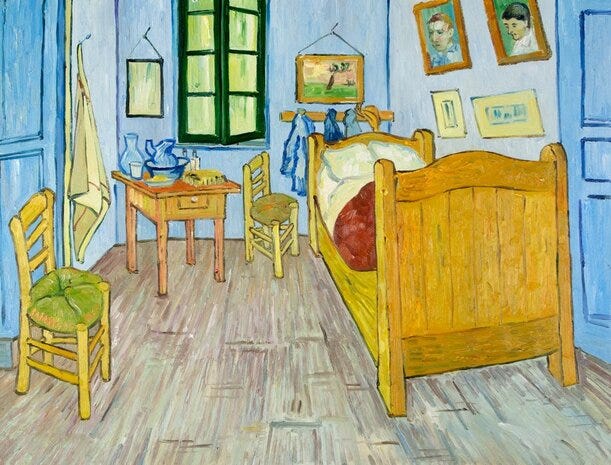

III. While living in the Yellow House with Gauguin, surrounded by yellow walls, Van Gogh painted “Room in Arles”. It’s on display in Paris at the Musée d'Orsay, and blu tacked to the wall of freshman dorm rooms across the country.

After an upperclassman delivered a dozen red roses to my freshman dorm, someone told me that upperclassman had raped a girl the year ahead of me. I only half believed the girl.

A few weeks later, I was in his dorm room, doing shots of tequila. The last I remember is sucking on my teeth thinking to myself, just try it motherfucker before blacking out. Later, I learned my friend Cindy came for me in time, walked me home. But I was too drunk to lock my dorm room, and I woke up with another guy I knew lying at the foot of my bed, like a Labrador. An unlocked door, an open invitation.

IV. The winter sun sharp like lemon, I was pushing my five-month-old and two-year-old’s double-stroller into it, filling a morning when the call came in. “Liss—“ first the words were hard to understand, then they wouldn’t make sense. No no no not this one. I threw the babies in the back and drove. She walked out of the hospital, so young, even her gait a betrayal. When she’d asked for the rape kit, the nurse said, “you know they’re not that reliable. You should’ve come first thing.”

I held her, stroked her hair. Mia, Mia, Mia, Mia.

V. I read a student essay once, about being raped walking home from soccer practice, hidden behind a yellow maple. She wrote the whole thing in second person.

VI. Sophomore year of college, I dated a Pearl Jam fan who’d sing “Yellow Ledbetter”, roaring louder and louder, when he was drunk. He read a lot of T.S. Eliot, too, and revealed in whispers his father’s neglect and abuse. He fell into rages when I talked to other guys. He was a series of contradictions I didn’t know the pattern of then, and the puzzle of him kept me coming back.

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.1

We’d leave parties together and go for long meandering walks across campus late at night. One night, when we snuck in the back of the chapel, an argument erupted. They always came on fast. I can’t remember the trigger, but I remember his rage. Didn’t see the punch, heard the firework of glass, felt it like a soft hail at my back. A round hook, not to my face, but to the stained glass door beside me.

How pale and lazy we become in the shades of others’ rage, like buttercups living cheerfully underboot, shades of what blossoms.

He’d track me across an ocean to spit “whore whore whore” over Thanksgiving abroad, my little brother bearing witness.

VII. There’s a story I hate about my friend’s mom making tuna fish pretending it’s fine, fine, everything's fine, but her husband came home waving a gun and she’d hid the kids in the basement. Cut yellow onions so tears would flow, appease him with her sorrow.

And sometimes chopping onions, the thought rises up: what it means to hold a knife that might save your child’s life from his father’s fury.

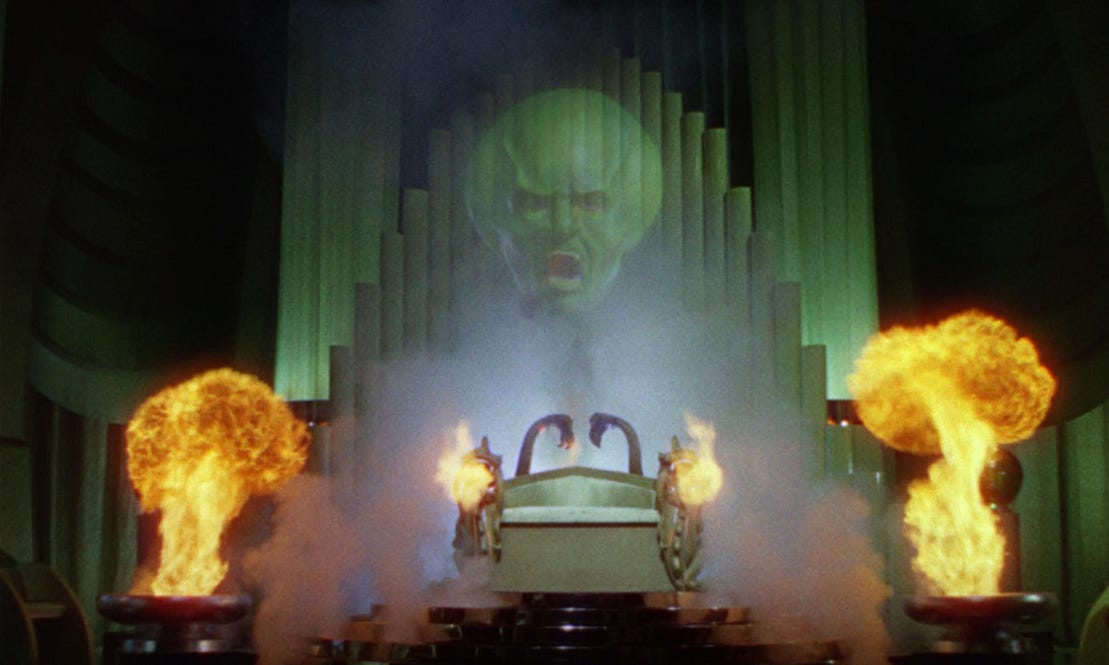

Before she realizes the wizard is a small fearful man behind a curtain, when his face looms large and green behind yellow licking flames, Dorothy answers the thundering voice: “I am Dorothy, the small and meek.”

But here’s the thing: she’s the only one to speak. In fact, the Tin Man, the Scarecrow, the Lion push her forward, and remain trembling, behind her, away from the flames.

When Prometheus gifted man fire so that our species would survive—much to Zeus’s rage who wanted to create a better, less feeble species—he hid it in a fennel stalk. If you’ve been to Cretan mountains in springtime, you can see what a good disguise this was: the licorice bite is gone in the soft fern of it, but the bushes are aflame with yellow flowers.

Yellow fire is a result of unburned carbon, carbon released instead of fully ignited, starved of oxygen and so incompletely combusted, the one that got away.

Yellow is a color of survival, not safety. The color of keys between knuckles. The color of locking the basement door. The color in your body, a decade, five decades later.

All the women in my life who have experienced assault were assaulted by men they knew. Men invited in. Over 80% of sexual assaults are at the hands of known entities. A friend, a boyfriend, a relative, a coach, a colleague, an uncle, a director, a husband. And this is just based on reported statistics. Assaults by domestic partners, friends, family are also far less likely to be reported.

None of those I’ve written about here were reported.

I didn’t want to make this essay about men. I wanted the voices to belong to women. But of course, it is about men. About their inability to hear all of these women’s voices. To believe their words, their experiences. To believe them as wholly human. And not just because they’re your mom or your sister or your daughter or your girlfriend or your grandma. Unattached from all of those relations: human.

I live in a liberal bubble, surrounded by more self-proclaimed feminist men than I can count on both hands. But men were conspicuously absent in the conversations chronicled here, even as they play the leading role. The answer is not in self-defense classes or curfews or baggy clothing or pepper spray. That’s like trying to curb global warming by reusing a plastic bag.

Like always, the problem and the solution are in the same place. The same people.

As the Andrew Tate’s of this world gain traction, convince in their crudely drawn promises of patriarchy a role that requires little more than barbells and self-affirmation, the empathy gap in men, young men particularly, is only growing. Other men— Scarecrows, Tin Men, Lions, et al— need to step forward, speak up, educate, counteract. Have a brain, have a heart, have courage. Care more.

Male violence is stage left, at the ready, in all of this, in our pasts that we can’t shake, in our future fears for our children, in my hands swinging at my sides instead of in my pockets tomorrow when I walk home alone after seeing a play with friends. We rarely see it coming, but we always know it’s there.

As we watched the movie on Friday, I looked at my sons, stilled by the music, absorbed by the celluloid spectacle, a pile of arms and legs on the couch around me. But there is violence in them, too, as there is in me. They kick and bite and hit and slap and punch, as children do. But they are male. And I try to hide my fear of how their violence might graft itself to something bigger, meaner, simpler, more insecure.

And they are, I know, also the answer to all of this. Unfair as that might be.

At the end, Dorothy, learning the power was in her the whole time, returns home safely to her sepia world. But no one understands where she’s been. Worse than not understanding— the haunting question arises:

“Doesn’t anybody believe me?” Dorothy asks the adults in the room.

And, in that moment, I know how important it is that my boys do believe her.

from “The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot