My Sister’s House

a love story in the South Downs

Phoebe said she would book the tickets herself.

Because I was still in the US taking care of my kids, and when I returned, I’d take care of the lodging and train tickets. Planning our trip to Virginia Woolf’s Monk’s House—part pilgrimage, part literary LARPing—revealed that each of us has thought the other looks a bit like Woolf. It’s not a surprise, really, women in love with Woolf might see her in long-nosed women they love. Still, a delight.

Before we begin, a few things to know:

Neither of us is good at small talk. She introduced herself to me saying “I grew up on a mountain.”

She has lived in all of London’s most romantic neighborhoods—Notting Hill, Primrose, Holborn; I have not.

Having been raised on a mountain, Phoebe’s weather is often not my weather. Her views are not my views. She sees more, reminds me, gently, of my myopia. She’s got a playwright and poet’s sensibilities. Aware of everyone on stage, sensitive to even the smallest of gestures, like the woman who scratches her wrist or the man who flicks his thumb with his index finger.

We work in the same office but there is one person between us and sometimes it feels like sacrilege, this person’s presence between us. But also, it’s how work gets done.

My mother wanted to name me Phoebe. How attached we become to the choices our parents almost made.

Phoebe plays violin on my child’s half-size violin when she comes over, surprising herself with what she remembers.

She is desperately in love with her boyfriend; she shared with me a 20-page love letter she wrote and, reading it made my love for my husband, his for me, feel shriveled and tired.

We are both sensitive, but she more than I. Her body navigating energy and emotion at a higher frequency than anyone I know. Sometimes I think she feels things for people before they’re aware of feeling them themselves.

There is a bit of fairytale and a bit of tragedy about her at all times, like a cloak.

When I write, I have two readers in mind. She is one of them.

It is something more than friendship. Akin to sisterhood. She named herself sister to me, I named her godmother to my youngest, securing one another in the rest of our lives.

Leading up to my fortieth, I set out to write forty letters of gratitude to the women who helped form me into middle age: my dead grandmother, my mother, my thesis advisor, my oldest friend, my nanny, the woman whose apartment I went to after I was assaulted. Some of them are still on my dresser, five years later, waiting for an address. I was a few shy of forty. But I met her, on Skype, the month I wrote them, and so when Phoebe turned thirty and her boyfriend asked us to write something for her, I wrote her one of those missing letters. As if time and endurance knew.

She is a person of pockets. For her 30th birthday, I also gave her a jacket my mother had given me on my 30th, but I sewed more pockets inside and left a stone for each of her decades, the decade to come. We’re both stones-in-pockets kind of women, but not the kind you need to worry about.

She has brought me a lemon from Spain, a tile from Panama that I carry in my coat, gifted me a shirt of hers I said I liked, more books than I can catalog, and all her cards to me are in my vanity.

We went into lockdown when my fourth child was three weeks old, and Phoebe had a bottle of champagne delivered to my door.

In the height of Covid, we hugged on the corner of Finchley and Acacia Roads, making public our loneliness’s need.

She is over a decade younger than I, but staggered by the stairs.

A week after her thirtieth birthday, Phoebe got Covid.

Before she was sick with long Covid, Phoebe walked me home a lot. From school, from events, from parties. Buzzed, walking home from a party, June’s persistent sunlight insisting afternoon, we held hands down the high street like we were the Terminator and no one could get in our way. Besides my husband and my mom, she is the only adult I regularly hold hands with. After she dropped me at home, Phoebe sent a poem, “The Women Who Walk Us Home” by Kate Baer.

We are full of confessions for one another like young blushing lovers.

Our friendship lexicon is filled with Woolfisms: I reassured her need for rest with a reminder of the single best literary description of a nap, in Mrs. Dalloway. The passage ends with the sibilant triptych “So she slept,” as final and comforting as the hushing old bunny in the Great Green Room. Virginia was also a big napper.

When we’ve forgotten deodorant, it’s always when the other’s also forgotten deodorant. We are good company, even when we’re not for others.

Last autumn, we foraged for rosehips, and I made her syrup—rosehips have an embarrassing amount of vitamin c in them—a gift to make her better or give me hope she might feel healthier. It is so silly and so necessary, this will we have to make those we love healthy, even as we’re sometimes making it worse, letting them expend their last bits of energy when it’s focused on us.

She is a self-proclaimed bear: forager, lumberer, wild-haired and back-scratching on a tree. Now hibernating.

We are not the best travel companions, she and I. We’re Type B people. I screwed up the timetables, we almost missed our trains going and coming. Items were forgotten, lost along the way.

When Virginia Woolf invited T.S. Eliot to Monk’s House, she wrote “bring no clothes.” A finicky man, he insisted on vests and ties, but she encouraged slouchiness. “Bring No Clothes” became our running joke; like Virginia, we dislike fashion but love clothes. All the same, I text Phoebe a warning before I kiss my boys goodbye: “I’m bringing clothes.”

At Victoria Station I am in felt hat, pearls, vest, and a bag much bigger than an overnight demands. I’m absurd. But then she meets me, also vested, her bag equally big, winded but ready.

There is a strange thing that happens in long Covid called wired and tired. Phoebe describes it as a frenzied casing around deep fatigue; even in her giddiness, she feels the bone weariness lurking. It will come. It always comes. I’m looking for it in our weekend away.

Monk’s House is tucked away on “The Street” in Rodmell, a 10-minute drive from Lewes Train Station. It’s your English village fantasy: roadside bushes dripping in honeysuckle, everything smelling of orange blossoms. The church down the road is a Saxon round-tower. And a thatch roof cottage next to our bed & breakfast is for sale.

When we arrive at Monk’s House, Phoebe asks the woman taking our tickets, “who looks more like Virginia Woolf?” The woman looks closely at us, we give her our profiles. “I see different aspects of her in both of you.” Our weekend of being as Virginia as we can be is off to a good start.

The Woolfs loved to walk the downs, and it was on one of their walks they came upon Monk’s House. A 16th-century cottage, there was no hot water, no electricity, no toilet, but the view of the downs feels both intimate and infinite. Leonard developed a green thumb, and the National Trust has done its damndest to keep it up. An Eden, the garden is aflame in mid-September with dahlias and sunflowers and canna lilies and black roses, water lilies in the ponds, and the orchard provides us our picnic lunch: raspberries, apples, pears, cucumbers.

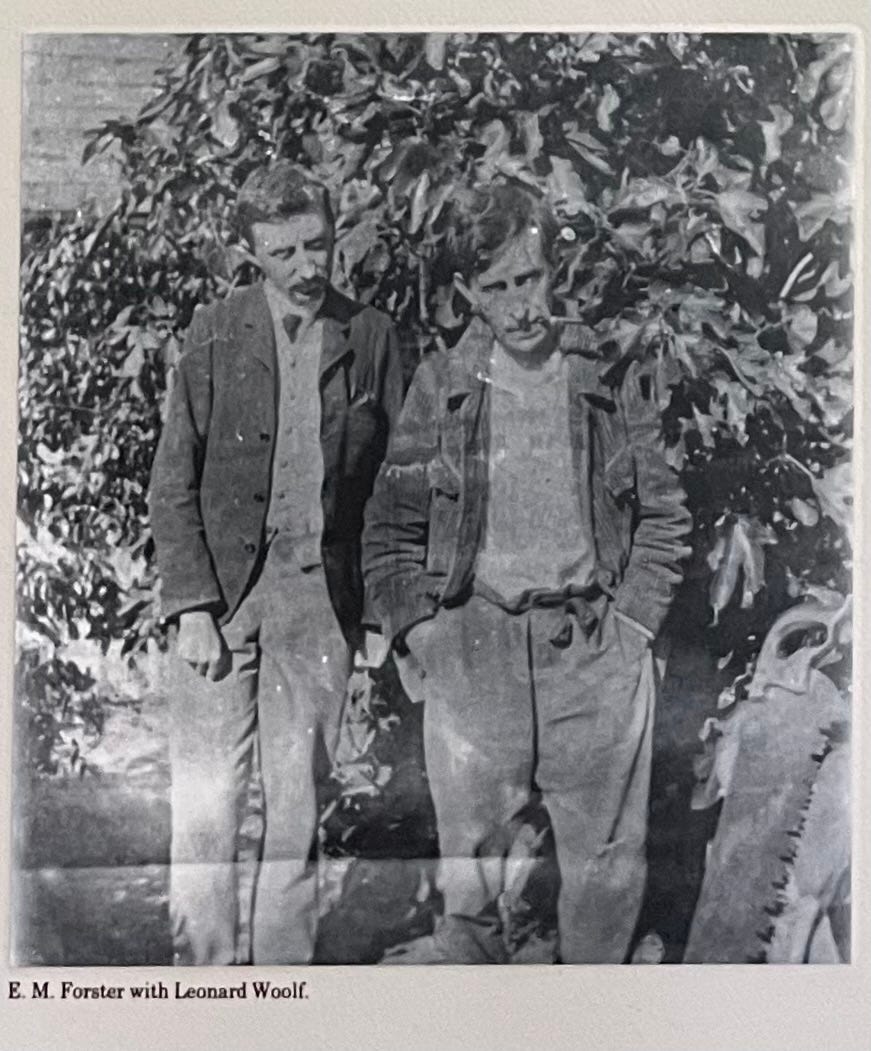

On the lawn overlooking the downs, sitting next to a basket of bocce balls, Phoebe reads to me from Woolf’s biography, a letter E.M. Forster wrote about his stay in 1934.

In his letter, Forster grumbles, “I was irritated at being left so much ‘to myself’ … Here are [the Woolfs], who read [newspapers] and then retired to literary studies to write till lunch.”

The letter gets funnier, vindictive, everyone begins to get churlish and childlike: Leonard finally comes out, but then Forster refuses to engage, continues writing his letter petulantly and documenting his choice to do so, and Leonard angrily saws dead wood out of a buddleia. Then Virginia arrives, fresh from her literary morning, “to suggest a photograph should be taken.”

“It must be that photograph!” I interrupt.

We laughed earlier at a picture of Forster and Leonard, looking as dispassionate about a photograph as two subjects can look.

And when she looks again, Phoebe says, “Yes! There’s the saw!”

What Leonard and Virginia really loved, more than the visits, the games, the conversations, was the solitude of their South Downs home. And we can’t believe our luck, we have Monk’s House almost entirely to ourselves. There is an older man peering into a lily pond, hands folded behind his back. There’s a young woman looking at her phone, head in the lap of a boyfriend who stares off at the downs. We are all relieved to idle.

That evening, at the Abergavenny Arms, Phoebe, filled with errant lines, has worked out what Woolf would order. “She wrote in her diaries of haddock and sausage: ‘And now with some pleasure I find that it's seven; and must cook dinner. haddock and sausage meat. I think it is true that one gains a certain hold on sausage and haddock by writing them down.’”

We order fish and chips, a Sussex smokie, port and sticky toffee pudding, sure that this is what Virginia would’ve ordered.

There are writers who have claimed Woolf had an eating disorder as a result of the traumatizing molestation by her older step-brother. But her diaries are also filled with food and joy and the way sunlight loves a hay field, and we’re reluctant to define her lifetime of eating habits by someone else’s claims.

Woolf attempted suicide a few times before she was successful. But after the Blitz destroyed her London home, she fell into a severe depression. On March 28, she put large stones in her pockets, walked into the River Ouse, and her body was recovered 21 days later.

On our second day, the plan is to walk to the River Ouse, and there is no one I trust more to go delicately than Phoebe. I will follow her lead.

Like all rivers, it’s tricky to understand the river on a map from the river on a landscape, it swoops and zags and what feels close becomes far. We go the wrong way and find ourselves farther from the river. Instead of by the river, we are again behind Monk's House and the church cemetery. Phoebe picks up two shards of pottery in the path, gives one to me and pockets the other, wordless.

In her diary, Woolf notes: “One can’t write directly about the soul. Looked at, it vanishes; but look at the ceiling, at Grizzle, at the cheaper beasts in the Zoo which are exposed to walkers in Regent’s Park, and the soul slips in.” In noticing, we find our souls, or some piece of them.

Phoebe and I take breaks. Which gives time to notice but also I’m looking at her, pacing myself to what her breath tells me she needs, and still I know I’m failing to notice sometimes. I’d give her oxygen if I could, a tree, a forest.

Walking through field and down, we spin out projects and dreams that include one another, guarantee us shared time and space. Simple collages, linographs for her wedding invitations, reading all of Woolf’s diaries, but also an essay or book or podcast titled Great Women’s Houses in response to Woolf’s sardonic “Great Men’s Houses.” And the dream: to buy Woolf’s former home in St Ives, and make it what it should be: another Woolf museum and place of respite. A place to convalesce.

The wind whips up just before we reach the river, the sky a looming grey, the tide rising and as we pull off our clothes on the rocks, we are all goose flesh. The grasses are waving at us in the wind, their blueness revealing itself. My towel is blue, her suit is green, and it all feels so fluid: our health, our love, our sanity.

Phoebe wrote a poem titled “how do we undrown the women,” and I think: here on the banks of the River Ouse, we are looking for the answer.

We climb and slip down clay and rock to come to water’s edge. I scramble back up to retrieve a gift. I’d been in a bookstore, trying to find Olivia Laing’s To the River, recommended by a friend when I told him of this pilgrimage. A flinty-voiced woman ahead of me, young and unserious, kept piling small polished stones on the counter. When I arrived at the counter, I stopped judging. They were stones polished into hearts, silly and maudlin and perfect. I bought four.

We enter the water, a stone for each hand, but I don’t have water shoes and I’m slipping. Phoebe transfers the stones to her right hand and takes my right in her left and we plunge. “The flap of a wave; the kiss of a wave; chill and sharp and yet […] solemn.”1 The water is cold and the current reckless, we break apart to swim upwards, swim hard to get back to standing.

The brackishness of the water is surprising to both of us, we’re closer to the sea than we thought. It reminds me of Woolf’s final entry. 24 March, 1941. In the entry she is concerned about a woman who’s lost two sons in the war, a woman with whom she can’t bridge an icy gulf, no matter the niceties. Then she writes,

“A curious sea side feeling in the air today. It reminds me of lodgings on a parade at Easter. Everyone leaning against the wind, nipped & silenced. All pulp removed. This windy corner. And Nessa is at Brighton, & I am imagining how it’d be if we could infuse souls.”

Her sister, Vanessa, away in Brighton seems to be a part of all this “pulp removed” for Virginia, and I’m again grateful to have Phoebe beside me in this river.

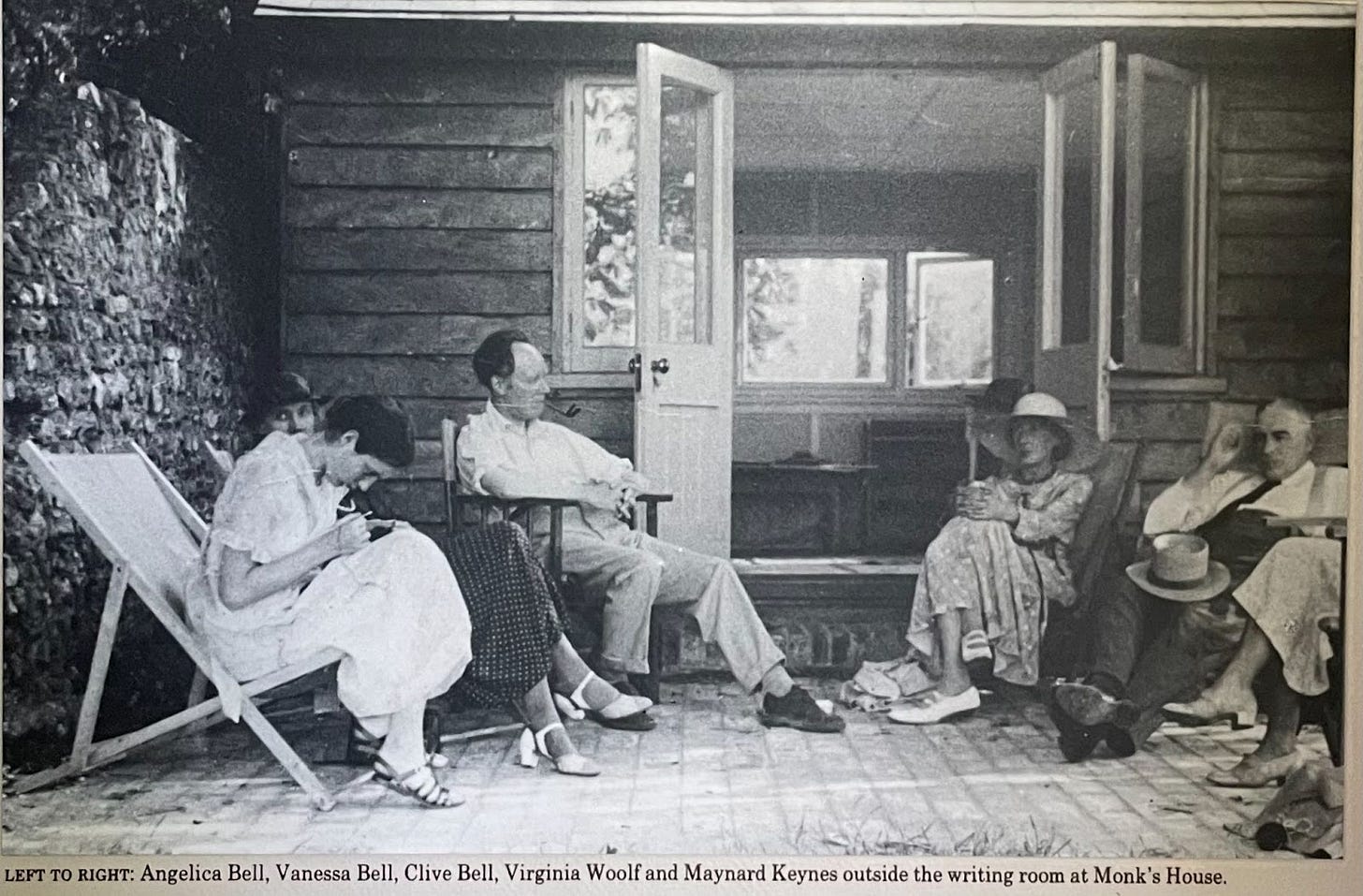

When we are in the water, Phoebe says she can imagine the reasons one might come here to die. She has never had suicide ideation, a statement I pocket like a promise, but she can imagine it. And when she walked in Monk’s House yesterday, she could see how Virginia lumbered through it. They’re the same height, Phoebe insists. But when I look it up later, I learn Virginia is my height. My secret. In photographs, she moves like a taller person. In Woolf’s writing lodge behind Monk’s House, there is a photograph of Virginia with Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell and Maynard Keynes on the patio just outside the writing room. In the photo, her legs are crossed just as so many times I’ve seen Phoebe’s crossed, like grasshoppers legs, one foot curled inward on the floor, the other crossed and running parallel, her hands hitching the knee up as if to make room for others. And indeed, Keynes and Clive Bell’s legs are sprawled on either side of a tucked Woolf.

Phoebe is tall and in her illness, clumsy. But she is anything but clumsy in her words and her connections; she charms everyone. The two old men walking along the River Ouse as we readied to plunge, look at Phoebe on their return and say together, “You did it!”

“We did,” she replies.

Our innkeeper Pauline, a jazz singer turned journalist who still submits all her articles in handwritten cursive, interrupts conversation to tell Phoebe she reminds her of her goddaughter. And when she says goodbye to us, she rubs Phoebe’s arm as if asking her to stay. And I can’t blame her, I never want Phoebe to leave, even in my moments of desperate solitude. We agree that goodbyes at the tube station are best for us (and they are frequent, she going into the city and me going out of the city home, after work), they force an end but also allow for high drama.

For a brief moment, we stand naked on the Downs, exposed. Some essentials have been forgotten, like underwear, but that should have been expected. When dressed enough, we climb back up to watch our river and eat the cucumbers stowed in our bags from Monk’s House the day before. The energy from the cold water begins to ebb, and Phoebe begins to speak of fatigue. We head back, making a berth for two large cows resting in the path. The rain begins, a mist and then a dousing. We were dressed for sun but not for this and we don’t move quickly, so by the time we tumble into the harbor of the Abergavenny, we are soaked. Largely pescatarians, we order hamburger and chicken.

My friend is sick. She has been sick for almost two years. And she is young. So she has been sick for 1/16th of her life. Before this, she biked every day to work, played epic tag games with my kids, hiked mountains. I’ve learned—I am learning—there are words that are unhelpful: “you look so healthy!”; “You seem so much better!”; “Are you feeling better?” It’s not a straight trajectory, and to name it as such in a question or statement to a chronically ill person is like waking from a dream to loss.

Phoebe has loved Woolf since well before her illness, but in her illness she’s tapped a deeper kinship. In 1926, Woolf wrote “On Being Ill,” an essay beseeching writers to write about the “drama of the body,” and more specifically, the body in sickness. “[L]iterature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind,” but our bodies are our frame of reference, with us until the end. And yet in literature “there is no record.”

The body, too, can be lyric.

Recently, Phoebe shared with me a piece she wrote chronicling her study of disability theory. Of Crip-Time, she wrote:

My mind learns the term long after my body learns the concept I do not wish to claim “disabled” let alone appropriate “crip” but we have moved into their neighborhood or maybe their time zone my body mind and me, the time warp trio, timeless wonder and the good news is we’re no fascists cuz you can bet our trains don’t run on time ‘round here.

[...]

I explain it to the technician attaching ECG pads to my bare chest, my bra beside me: It’s like I can’t ever catch my breath fully, the world’s on hyperspeed, my brain is fogging up, and it’s all just so exhausting I need more rest, need more rest, and I don’t know why. And what she says, here in this doctor’s office, is “well is long Covid even a real thing? And if it is, what do you expect a doctor to do about it?” And I sit there, a half naked time traveler, watching my heart rate rise.

I explain it to my mother: It’s like when we lived on the mountain and our school was in the valley and we would call in to tell them “we’re all snowed in” and they would say “no you’re not, there’s no snow here,” and we would have to explain some science.

But none of these get me to “crip time,” just what happens when compulsory able-bodiedness can’t fathom that “time is out of joint,” that “there’s no clock in the forest,” there’s just this geologic time scale and me, measuring out units of rest.

When climbing stairs with Phoebe, I listen for her breath to snag, become ragged. There’s a smile she gets when she needs to stop. I’ve come to know it. It’s rueful, full of discomfort for slowing her companion down. She puts her hand to her heart, as if comforting it and herself. She has a pronounced sternum, as if her heart is too big for her body. Sometimes, when she trusts you, trusts that the clock matters less than she does to you, she will put her arm through your arm for the rest of the journey upward.

I am moving slowly here. Her body has given definition to this essay.

Part of writing about illness is mitigating shame, part of it is ensuring there is language enough, and part, as Woolf and Phoebe name, is putting it in print so it can be believed.

At a gift shop near the station, Phoebe puts “The Journey to My Sister’s House” in my hands. It’s a pamphlet of Woolf’s diaries in collage chronicling the five-mile walk Virginia took to her sister Vanessa’s house, Charleston, in Firle. Before I purchase, Phoebe asks me, “do you think we’re actually Virginia and Vanessa?” And I think how uncontainable and how answering this friendship is to the question Woolf asked in her final diary entry: “how it’d be if we could infuse souls.”

We say goodbye on the platform of Green Park. I am taking the Jubilee northbound; she is taking the Piccadilly eastbound. Phoebe is exhausted, her body contracting in on itself, her eyes filmy, all the energy she had, she’s given to me. Yes, I am guilty, but I also know—she has promised it—she won’t drown.

And when she’s well, we’ll walk the whole of the South Downs together, all the way to the sea.

from Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway

I love you, Virginia. And I could not be more honored to be in your life and writing. It was the pilgrimage of a lifetime, and it was only the first annual. See you in St. Ives, or on the writing lodge porch of our dreams, or just down the desk from you tomorrow <3 <3 <3

This was so beautiful!

I particularly loved this bullet:

“My mother wanted to name me Phoebe. How attached we become to the choices our parents almost made.”

♥️