Parentagonist

parental rage and the characters we enact

Right after intermission, still smacking our lips on Dairy Milk chocolate, we watched the Grand High Witch perform her bedroom moment. “This is for all the parents in the crowd,” she cooed. I sat up; my children remained hunched, chins resting on forearms, peering down from our balcony seats at the stage. The Grand High Witch’s song “Wouldn’t It Be Nice?” chronicles the freedoms parents might relish were their darlings simply to disappear. Sleeping in. Going out. Pursuing hobbies. Eating a plate of food without the interruption of picking fingers. Realizing potential. Her arms are expansive, robed in purple metallics; she is alone and she is majestic: the physical manifestation for all of us adults, looking up from the stalls and down from the balcony, hungry with the promise.

Imagining them all—all my pretty ones—just gone, a sob burped out of me. For the relief of it.

Roald Dahl’s stories are filled with terrifying adults, magnificently drawn even in their crudeness—the Witches, the Twits, Trunchbull, the Aunts—and while they’re fantastical, the truth at the center of his stories is that a child’s relationship with adults is ever precarious. A child understands just how little power he has.

My second-grade teacher, Mr. Snyder, introduced me to Roald Dahl’s The Witches during post-recess reading circle. We sat on the rug, and he sat above us, on a wooden chair with a cushion, and read for 30 minutes. My favorite part of each day. I was new to the school, new to the country that year and these stories were my escape.

As he read, I knew I’d never make a Dahl hero: I wasn’t an orphan, I wasn’t an abused genius, I wasn’t stoic, and I wasn’t really all that sweet. Sophie, Matilda, Danny, Charlie: I liked them, but I never saw myself in them. The closest I could get to a Roald Dahl protagonist was finding myself an antagonist.

Which I did. Mr. Snyder, the teacher who delivered the scary stories, became the scary adult in my life, my Ms. Trunchbull. Unlike Trunchbull who threw children out windows, sent them to “the chokey”, flung darts at their photos, Mr. Snyder didn’t hate children. His disdain felt particular to me. There was no one thing he did, I could just sense his contempt for me from the beginning, scolding me more than others, casting me disapproving looks, sending me to the principal’s office. I was bossy, had a wretched haircut (the result of my mother’s rage against lice—my forgiveness is still in process), glow-in-the-dark Reebok hightops that I flaunted. I wanted to be in the center of the conflict. And where there was none, I was obliged to create it.

His antagonism lent me a mantle: I was an imperfect heroine, inspiring a recess game of “dodge the pancake” with the pancakes he’d made us; I purloined a sequins tank top from my mother’s closet, threw it on in the girls’ bathroom, and nipples out, strutted into the classroom, refusing to change; I rallied kids to stage a revolt during a math lesson. I was highly annoying and felt entirely justified.

I wasn’t good and I wasn’t interested in being good. I wanted to be loved for more than goodness, I wanted to be loved in spite of my badness.

In 2020, I came back to Dahl for the first time since childhood as the pandemic raged and the ‘70s admission of mom rage came roaring back like bell bottoms. I was coursing through the Roald Dahl collection with my then seven-and five-years olds, feeling grateful that as the world fell apart around us, I was not filled with rage or fear or anxiety. With a newborn in the house, I was tired, yes, but I was spending time in nature, doing creative projects with my kids, recognizing the possibilities that this cocoon of time offered our new family of six. I was a little smug. Now, I am entering my third pass through Dahl’s oeuvre: with my youngest two. And this time has been a lesson for my own antagonism.

Here’s the thing: I’ve been avoiding this essay. The nowness of it hurts.

In Boy, Dahl mentions the shape all adults take to children “as giants.” I’m reminded of it when my children’s small hands point to Quentin Blake’s illustrations, on the pages of the book I hold in my own giant ones. But there is also the funhouse mirror of parenthood. I’m both shrunk by the task and made large by it.

My first decade of parenting, the most regular compliment I’d get was “you’re so patient,” which never felt like much of a compliment until I stopped receiving it. In this last year, patience has left me. It took longer for the rage of 2020 to find me, but in the last year, it has increasingly filled me. Most often, it boils out on the morning commute to school or just before bedtime. Transitions of course. And it frequently has a target: my third, my most stubborn, my most demanding.

Earlier this year, I had a recurring fantasy of Nicholas, sulkily driving his toe into the ground with each step, being kidnapped. I imagined the hassle of paperwork followed by relief. Minna Dubin, author of the viral mom-rage essay republished in April 2020, revealed her mantra in rage is: “don’t touch him don’t touch him don’t touch him.” In September, I walked a half block ahead of my five-year-old, letting him navigate two suburban street crossings without me, so I could mutter “fuck you fuck you fuck you.” I was breaking maternal law, I knew, but also saving my child from myself.

Some days, in order to get to school on time, I pull him, my hand around his forearm, to our Tube stop, drag him really, and he trots, not to keep up with me, but to keep from falling.

There’s his stubbornness, his need for constant stimulation, but that’s not where my rage was born. Nicholas’s own rage found a target in his younger brother, and repeatedly trying to protect my youngest from him, mine grew. Lately, I protect one young child from harm by harming my other, the source of his harm. And as Nicholas is learning to regulate his emotions, I’m learning new hormone levels in perimenopause. Our rage has filled the Venn diagram of us.

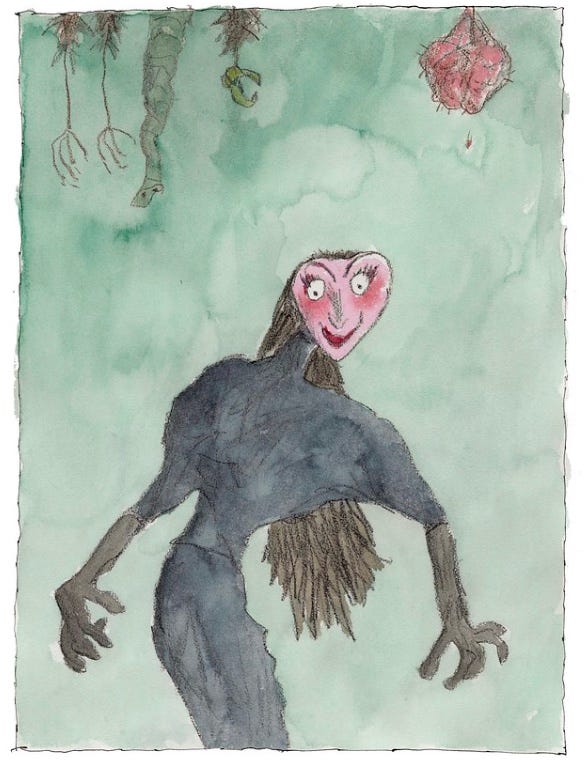

Nicholas’s feelings, too big for his body, pump into mine, inflating me. I am a storybook villain, absurd in my rage, minimized and made large by my venom, bloating even as I am made smaller by this singular emotion that controls me. I am boiling water, Ursula emerging, a genie’s release.

The rage is spilling out and onto my other children, too. My youngest demanded a different cup, a different milk than the one I’d just given him, and I delivered it back again, but this time, I slammed it on the table in front of him, the cork pop of melamine on wood. The milk slopping out hung in the air momentarily like a magic trick, a puddle spilling upward. And I knew, even as I made it, the spill would cause my fastidious child to cry.

There’s the more frequent yanking of sweaters over heads, enraged hands enacting care, collar catching at the crown of their heads, and the continued forcing, their hair flopping back and forth, like diving ducks. It’s absurd, almost funny, as most brutality is.

Looking back at my moments of rage is like looking at photo stills. The memory is precise and filled with contour. The hangover of it—acid reflux—has found me.

Last month, getting ready for the airport, two days from his sixth birthday, Nicholas refused to dress himself. And counter to what all my experience in standoffs with a willful child has taught me, I insisted he do it himself. He didn’t. For 20 minutes, he refused. We were going to miss our flight so I did it for him, roughly, and then my husband took over. Standing in the cold, all my children were climbing in or next to the car, crying, and my arms were flapping in my long black coat like a human bat. My words threatening, about their ingratitude, their impossible lack of generosity and maturity.

Later, I climbed to the back of the airport bus where my eldest sat alone and away from our emotions, to apologize. He was wooden and a cold fear touched me: was this the moment I lost him? A true oldest child, he had borne witness to my rage, obliged my threats and name-calling by accommodating my demands, the only one of them to do so, and his face was closed to me. I am not the mom I was even a year ago, and he’s old enough to know it. I put my arm around his shoulders, they stiffened, but he let me stay there, didn’t shrug me off. And I breathed out.

Even as it feels bad, it feels good. To feel so deeply and purely one thing, the cacophony fades, pretense fades, and I surrender to it, fall into the emotion, unrecognizable, even to myself. That surrender is a form of relief.

This rage comes from a place of need, but it’s also an indulgence.

We get dopamine from rage; in the past, it’s secured survival. With dopamine on our side, we won the competition for resources. And while it was once believed we were hard-wired toward or against rage, neuroscientists now see there’s more plasticity to it. Because of repeated exposure, for example, we might become more aggressive and rageful in response to experiences. Stress is the natural reaction to stressful cues in our environment, like a shrieking child who won’t stop.

Nicholas has always been precocious, “twice exceptional” as they say, more Matilda than the rest of us. A few years ago, I told a good friend over a bottle of wine that I was proud to be his mom, because of how clever he is. That still haunts me, that somehow my brag was the reason for all the challenges we’ve had since, his truculence, our twinned rage, how powerless I feel, how powerless he is. I have begun to gravitate toward other parents with challenging children. When a friend told my husband and me that he tore the head off a doll and yelled at it, to keep himself from the object of his fury (his own child), I felt giddy in my recognition.

My husband, once the less patient of the two of us, was the one to figure out the pattern to Nicholas’s rages. They last 30 minutes. Sometimes Ben sets a timer to help himself cope with our son. And if we hold Nicholas, even at the risk of our own body, he will show his thanks in his affection directly afterward. He collapses into the person who stuck it out with him, repeats how much he loves them.

It wasn’t until Ben named Nicholas’s pattern that I began to consider the pattern of my own rage. The heat, the engorgement, the bile, the monoemotion. And then the deluge of counter feelings: deep affection, guilt, regret, protection. There’s a dangerously addictive quality to penitence, and I don’t want to fall deeper into the habit.

Somehow, I have to remember that I’m the one with a developed prefrontal cortex in this relationship. The maternal instinct must override the reactive aggression.

******

My older children and I are reading Wicked right now. Every morning, I recount the previous night’s chapter to Nicholas on our walk to school. It’s one of the tricks to getting him out of the house these days: the promise of a story. It’s helped. From the first chapter and the description of her exceptionally pointy teeth, Nicholas saw himself in Elphaba. Nicholas, too, has strangely pointy teeth. The marks of which we have all borne on our limbs.

He sees himself in the antihero, the one tasked with controlling insuppressable emotion. As with most toddlers, Elsa was the first love of his life. And like Elsa, like all of us, Nicholas wants to be loved for more than goodness, he wants to be loved in spite of his anger.

Some early mornings, more often than his three brothers do, Nicholas patters in looking for company. He ropes an arm around my neck, threads fingers through my hair; I cup his body to my chest and stomach, his breath hot, cloying and comforting, against the nape of my neck. His inhale deep and private, his exhale bright and gushing, a furious spring, almost unbearable in its vulnerability. But our bodies make a sort of infinity, a promise not to leave, a promise of forgiveness even when it all feels impossible.

Alissa. Thank you for sharing so freely. I too am the parent of a twice exceptional child. My oldest, C, is and has been and will always be his own unique joy and unique challenge. He engenders loyalty in so many ways from everyone who meets him, but rarely from a place of how good he can be.

I’ve also seen many of your experiences in my own life. I never ripped the head off a doll, but I certainly have thrown my fair share of stuffed animals at my kids. I’ve seen and felt the unadulterated rage coursing through my body, and my children know what it means to cuss like a sailor. But I’ll also go to hell and back to fight for them.

I had never really thought about those of us who want to be loved not because we are good, but in spite of our badness. We all just want to be allowed to be human, ourselves, without judgment and with unconditional love.

"I wasn’t good and I wasn’t interested in being good. I wanted to be loved for more than goodness, I wanted to be loved in spite of my badness."

Picked out the same dime as Latham.

Alissa, this is so beautiful, so raw, and so reflective of the complex emotions inside of us, especially us parents. It's as if we are tightrope walkers, and the spar we hold in our hands reflects our range of feelings - joy, love, and happiness on one end, and rage, frustration and anger on the other.

When we become parents, the width of the spar increases by 10X - meaning the range of what we feel is so much greater, more intense, and downright scary. And we need to learn to contend with, manage, and embrace those feelings inside. Perhaps by the time we are becoming reasonable at doing so, our kids will be gone.

The life we live is the lesson we teach. When rage is running through my emotional system, I, like you and Latham, try and disrupt it, and not let my kids see it, so as to not pass it along to them. It's a struggle, one that I've lost, and one that I've won, one circumstance at a time. (two many ones/won in that sentence!)

Last, isn't it true that the essays that are our hardest to write, and the ones we put off, can be the most profound. Thank you for pushing through to the end of this. It will make me a better person and parent. And you will have invisibly impacted my daughters as a result.

As you feel and as Latham reflects as well,