Please manspread on my page

has anyone noticed men don’t really write about their bodies?

I’m on the hunt. Scouring my files for body parts.

Last autumn, I had an uncomfortable moment with a man I knew only online. We’d worked together, he’d edited and championed my writing, I’d read his essays weekly, a growing fan. I was on the tube in early October when his latest essay popped up on my phone. I clicked and read and bit the side of my thumb in discomfort. This man, who draws regularly on Rumi and Seneca, his time in the Navy, fatherhood, was writing about his body. And it felt strange. And I couldn’t make sense of the strangeness. I read about the body all the time; in fact, I don’t think I’ve written a personal essay that doesn’t include a body part or me thinking about my body. His essay opened: “For as long as I can remember, the highpoint of my health goals was to look good naked.”

Maybe it’s that I don’t read men’s health articles? I was meeting the limits of my male canon?

I hit like, hesitated over the comments’ box, clicked my phone off and slipped it back in my pocket. Did I like the essay?

I’ve talked to men about their bodies—colleagues, friends, brothers, sons, my husband—and I see men’s and boys’ bodies in various states of nakedness every day. And, yes, I’ve read a handful of literary men writing about their own bodies, but, as I thought about it in the days that followed, I realized they are few, and usually in poetry. And I’ve been trained well to know the speaker isn’t always the poet: so how much is this actually a man talking about his body after all?

I’ve come across many male writers writing about other men’s bodies—Montaigne writes generally of thumbs; Ta Nehisi Coates names the body over the 40 times as he talks about the danger of being a black male body in America in Between the World and Me; David Foster Wallace speaks universally and singularly about bodies of the average man and the superman Roger Federer in his essay “Roger Federer As Religious Experience”. And in “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again”, Wallace entered the “Best Legs” competition, a very brief and ironic nod to his own “gams’ shapeliness”.

But I know men are thinking not just of the universal, but about their singular bodies all the time. Where is the documentation of these feelings about calves and collar bones? We talk about manspreading in physical shared spaces, but in prose, I can’t find a man’s reflections on his own legs.

Am I stumbling into a silent taboo? Men not writing about their own bodies? Even as the personal writing of women is chock full of their own body parts, most men remain by and large disembodied minds on the page.

I dug deeper. Turned to history—literary history and my own. In order to complete my honors program in undergrad, I was assigned to read the British Romantics and American Transcendentalists, sent a list of twenty books, from Melville’s Moby Dick to Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound to read and prepare in the summer before senior year. In September, I sat before a panel of English professors, all men but my thesis advisor—a PhD in Victorian lit who asked her students to call her “Lisa”.

When I emerged from the panel and watched the men recede down the hallway, Lisa grabbed my arm. “You stood your ground, it was great, don’t worry: you don’t have to love Walt Whitman just because every one of those men in there worships him.”

Her voice was full of disdain, but also praise, and I’ve always been dazzled by praise. It wasn’t until later, in my apartment, that I realized I didn’t hate Whitman, in fact he’d been one of my favorites of the eleven men and one woman I’d read all summer. I realized it was just my inability to talk coherently or with any real substance that she’d taken my silence as blowing them off. I’d been nervous as hell, not recalcitrant.

Here’s what I love about Whitman: he writes about his body the way Michelangelo sculpted the body. With reverence and interest and compulsion. Which is to say, he acknowledges his body. And I’m so glad men read and delight in him, too. In his poem, “The Body”, Whitman begins:

That I am is of my body, and what identity I am, I owe to my body,

Of all that I have had, I have had nothing except through my body,

And what I should be I knew I should be of my body.

What belongs to me, that it does not yet spread in the spread of the universe, I owe to my body—

I comprehend no better life than the life of my body.

The word “body’ comes up 35 times, and seven of them are “my body”: that must be some kind of record. Thank god for Whitman.

I asked two of my male friends, two of the most prolific readers I know, for thoughts about this absence: is this a pattern, or is it a limitation of my reading? They also came up almost empty-handed, almost all of them reflections on athletic feats and a bit of poetry. It seems poets more than essayists make the impossibility of decoupling our physical experience and sensations from our ideas a part of their art.

There’s a lineage of women writers naming their parts in prose, especially beginning in the 20th century. And I began to wonder if the question is really what compels writers to write about their bodies? And further, is writing publicly about one’s own body a luxury? Or a necessity?

Are marginalized people more likely to write about their bodies? Does something about having your contours made obvious to you by others make you want to write about them? The few male writers I’ve encountered writing about their own bodies, gay and/or black, would suggest that may be the case.

We theorized—my friend Stephan wondered if Sontag’s “Illness as Metaphor” gave license and reason to some writers to focus the pen on the body? And perhaps more evidence of a compulsion to write about one’s own body when confronted with illness, injury, transformations: Whitman addresses his experience with injuries in the Civil War in “The Wound-Dresser”. Distress to the body, also, would certainly make sense for why women write more about their own bodies: our bodies are in monthly transition until post-menopause; it’s hard not to pay attention to them.

In a Zoom conversation with a man I’d just met, I was talking about my obsession to understand this absence: “Why aren’t men writing about their own bodies?” He answered, kindly, with a question, “Why do you care?”

The question stopped me. Why do I care that I can’t find many male writers writing about their bodies outside of athletics?

Why is it in absentia? What might it look like if men’s parts were in their stories? What does it mean to avoid looking at and discussing the body?

And, really, why do I care?

Maybe because I have four boys with four distinct body types. Maybe because my husband photographs our youngest son’s fingers everyday on the way to nursery and I understand part of what he loves about them is that they’re long like his dead father’s fingers. And I want someone writing about his own fingers that remind his father of his father’s.

Maybe because teenage boys are laughed at for mewing in classes, and they’re obviously thinking about their bodies all the time, and they’re feeling insecurities around body changes and body permanence, and I want them to read a diverse body of men writing varied and interesting things about their own male bodies. Just as we have a diverse range of women writers discussing their bodies in literature.

Maybe because one in three people struggling with eating disorders is male, but there is even more taboo in seeking help for it when you’re male.

Maybe because not writing about the physical body feels snobbish, a refusal to put the blue collar worker of a body aside the cerebral on the white page.

Maybe because a friend searched “men writing about their own bodies” when I spoke of my surprise, and what came up were links to men writing about women’s bodies, but when I searched “women writing about their own bodies”, links popped up about a range of ways women have approached and used their bodies in writing.

Maybe because I’ve spent 27 years reading and studying literary patterns, and I like a question without a clear answer.

Maybe because I think through men writing vulnerably about their bodies, more male readers will see all bodies as something to be respected.

Last week, I was in a brainstorming session with another man online. He was trying to get to what he wanted to write about, and in order to do so, he was walking me through his timeline. Then he mentioned his height: “I couldn’t fit in. And I was tall, too, and asked to do things I didn’t know how to do.”

“Yes, that’s it!” I shouted at him. “Talk more about your tall body, not fitting in, being asked to do things because the size of your body betrayed your ability! I want to read it!”

In a class discussion recently, one of my teenage students was bemoaning the phrase she hears most often from the boys in her life: “I want to get big.” She laughed and said, that’s like me saying, “I want to get small.” It’s weird, a nonspecific adjective to describe a hope, a wish, and an insecurity. Psychologists, health classes have agreed we need to use anatomical terms when talking about the body. Talking about the body more, not less, is healthy. So why isn’t there more first-person literature about what boys’ bodies can be and can feel like?

Yesterday, I put it to the other experts. Before class began, I asked my boys in 10th grade English, “do you or would you write about your body?” And the room exploded.

“My knees! I hate my knees!”

“No way my big Greek nose is making its way into my writing.”

“We can’t show body insecurities—we’d get wrecked.”

I’d phrased the question badly, and needed to rephrase: “I don’t mean the sole subject is your body, and it doesn’t have to be parts you’re uncomfortable with. It could be celebratory or totally neutral.”

One of my boys shouted, “I’ve written about my hand holding the pen!”1

One of my girls chimed in, “historically, women’s bodies have been written about by men, and there’s vulnerability in having your body in front of the camera or an essay. I think part of women writing about their bodies is an act of reclaiming their own bodies.”

And then, as the classroom settled back to our usual noise levels and civil discourse, voices no longer layered on other voices, one of my boys asked, “by just being spectators of other bodies, are we not putting our skin in the game?”

We’d taken a turn, together, to curiosity.

We ended with a bit of writing—not to share, just for them: what are the body parts you could write about? What are the parts you can’t write about?

When we finished, one of my boys said, “can I just say one more thing? I think it’s kinda about empathy—if you can’t humanize yourself, you’re not gonna humanize someone else.”

And then: “where can we have more conversations like this?”

In her final autobiographical works, Virginia Woolf wrote about the challenge of writing nonbeing into her work. Being is the stuff of action and causality; nonbeing is the mundane, the circular conversations, the naps, going to the bathroom, most daily needs and rituals of the body. The irony of course is a body is a being, there’s nothing more being than the body, alive in all its hangnails, bleeds, gurgles, breaks, excretions, floppy sloppiness. I’m greedy with the need to encounter conversations about one’s body on the page, in the most mundane of ways, in the ways Woolf would describe as nonbeing. And after weeks of conversation, I know I’m not alone.

One of my favorite comments from a rough draft of this essay was from a guy in my writing group: “When I was like 11 and some of the kids had really started puberty I remember how obsessed I was with growing hair. Going so far as to use mascara down there. I never wanted anything more than I wanted pubes. I think so much of the male body is about what it can produce. And we learn that young.” There is something so specific and so universal about this focus on pubic hair—it’s an image that smacks of adolescence, that slow time when we all want to hurry up and become.

In the last two years, the gender in literature class I teach has skewed dramatically toward girl-identifying students. And by dramatic, I mean I have had two boys in the class in two years. But this year, 16- and 17-year-old boys have come to talk to me about the class, telling me it’s their first choice for their senior year. And I want to be ready.

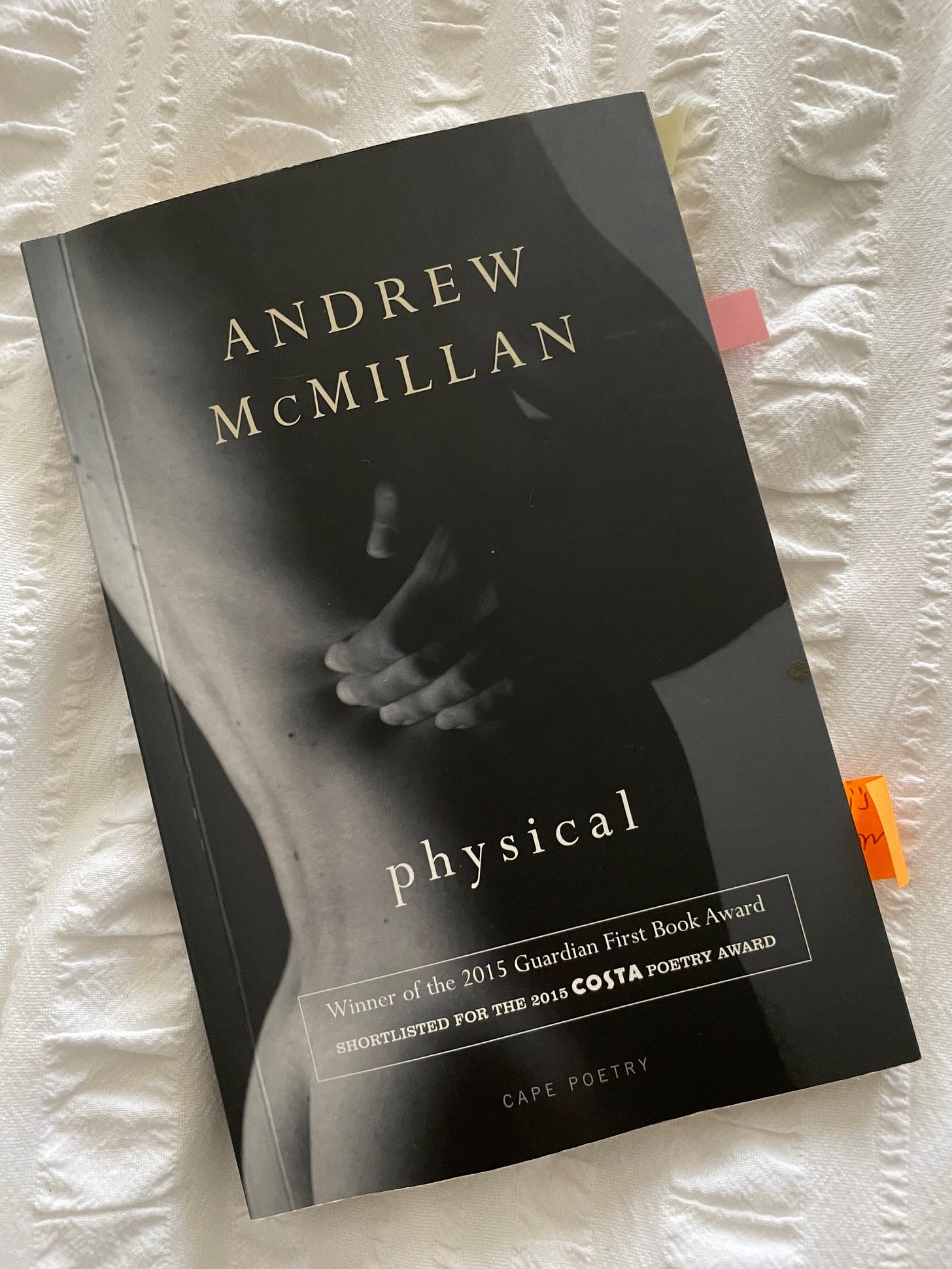

When their bodies are in the classroom, I want their bodies in the curriculum. Andrew McMillan’s collection of poetry will be there, as will Latham’s essay from October. Because I know the strangeness I felt was about coming upon new territory: a straight man speaking openly about his body on the page, not just in poetry, but in prose. To write about one’s own body publicly, to name the awkwardness and magic of the vehicle that transports us, is maybe, as my students taught me, also an act of courage, compassion, relief.

A sincere thank you to the many boys and men I spoke to while writing this essay, from ages 10 to 75. And to Latham Turner who made me wonder at the strangeness of a man’s own body on the page in his beautiful essay, and consented to my request to write about it so enthusiastically. Thank you to Anna Archakova Dara Songye Jeff Giesea Justin Lind kora kwok 🌊 Super Regular Matthew Hurley for taking the time to read, respond, and provide new insights on a rough draft of this essay. And to my reading friends for always handling my questions, quests, requests seriously and compassionately.

So many told me if they were to pick up the pen, what they would want to write about their own bodies and what they hope to never write or read about their own bodies. And I’ve asked many of them the question I’d like to ask all of you: what would it mean to you to read men’s reflections of their bodies on the page?

If you have in mind memoir, autobiography, personal essays by male writers exalting, defying, naming, rejecting, loving, confronting, putting their bodies on the page, as the subject or just a side piece, please share. And who knows? Maybe my future students will be their own examples.

He’s in good company: Seamus Heaney also writes about his finger and thumb clutching the pen in “Digging”

For me Theodore Roosevelt's autobiography has exactly this as he recounts his asthma and physical challenges early in life. His is father played a significant part in helping him over come those challenges in a loving way. Something that seems difficult at least for me to imagine in our modern age.

This puts me in mind of a lot of feminist academic philosophy that I read in university, which often noted how much more men tend to see their bodies as either a tool or as simply an unconsidered extension of their ‘selves’, as opposed to women who are forced constantly into an awareness of their body as an object in space which is open to observation. I wonder if an increase in male insecurity is a direct result of considering the body as an object in this way. When I feel best in my body, least insecure, it is because me and my body have become one thing, a purposeful and natural unfolding of agency. When I stop and ‘Look’ at my body however, I begin to feel things which I am sure every woman is familiar with. My crooked nose, the unflattering shapelessness of my arms, my sweaty hands, the placement of a freckle, my height. A body, perhaps, cannot be a marble statue and a vital, breathing thing at the same time. And therein lies our problem. We want to be both a crystalline perfection and a functioning being, and the former is an impossibility.