The Girl in the Window, the Woman on the Hill

how intensive journaling can access memory, creativity, personal growth

In my second year of teaching, a colleague introduced me to Ira Progoff’s Intensive Journal Method. The psychologist Carl Jung and Progoff worked together in the mid-20th century, a collaboration that informed Progoff’s journaling-as-psychotherapy approach. Progoff went on to create a series of 21 integrated journals to unlock people’s creativity and enhance their personal growth. While Progoff died in 1998, his adherents still offer workshops today, with a focus on helping participants with personal relationships, decision-making, transitions, and healing.

Over the years, this journaling has had the same immediate effect on my well-being as yoga and cold-water plunges. I love it. Even as I know all the prompts and their sequence, I’ve yet to predict what will come for me in a journaling session. Instead, I’ve learned to expect the unexpected.

For my students, in-class journals have been a means of generating ideas and providing relief. Often we journal on a day when we need just to write and be internal; other days it’s a first foray into a personal narrative or longer piece of writing. I tend to use two of Progoff’s journals to warm up and shake off the inhibitions.

The first is called a Period Log: it begins “Now is a time in my life when—“ and we freewrite without self-editing for four minutes.

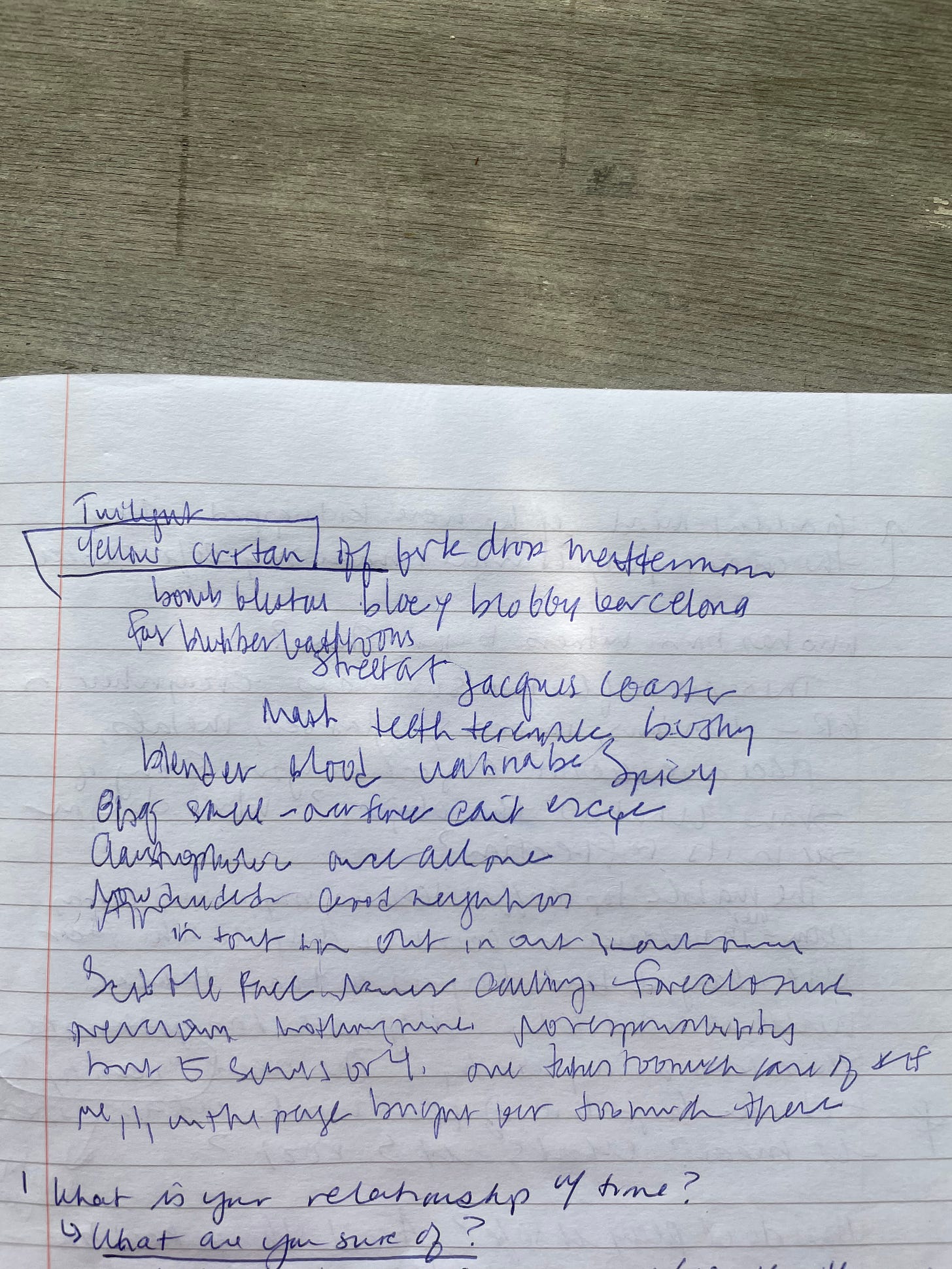

The second is called Twilight: we close our eyes or put them at half mast and write about whatever comes to mind for four minutes: images, sounds, shapes, colors, words. The idea with this second is to allow the subconscious to emerge.

After these eight minutes, I usually offer an original prompt, based on what we’ve been reading or discussing. This spring in London was like a winter hangover, so after a journal warm up, I wanted to get some music in the classroom. And since many of my students are in their last year of high school, I wanted to give them an opportunity to reflect on their former selves without bogging down in the usual innocence-to-experience schtick. Music stirs specific memories. Like a genie emerging from a rubbed lamp, out pops what’s been latent.

We took a few minutes to do each of the following and share, before arriving at #5 and entering our own writing worlds:

Recreate five of the songs on your 12-year-old self’s playlist.

Create a five-song playlist for the you of today.

Choose a song from each of the two playlists.

Choose a lyric from each of those two songs.

Write a personal piece that uses both of those lyrics in some way. (My pedestrian goal is to get multiple voices, specific objects in their writing. Of course, the narratives are much more than the sum of their voices and objects.)

I’ve hit play on my 12-year-old’s playlist, and I’m transported out of the classroom and into my adolescent bedroom.

The Spin Doctor’s Pocket Full of Kryptonite was the first cd I owned. I’d upgraded from a pink cassette player and George Michael, Janet Jackson, Paula Abdul tapes, to a large black Sony Boombox. Blind Melon, Arrested Development, 4 Non Blondes all neatly bedded in the satisfying vinyl thump of a cd storage folder.

“One, two princes kneel before you” played nonstop, as I fantasized about being worthy of two boys fighting over me. Josh Santos1, a boy I knew vaguely liked me and thus a reliable source of boy gossip, told me the story of his sleepover at Mark Miller’s house. Mark Miller lived on the street parallel to mine, and his alliterative name to this day makes it impossible not to say it in full. His house, big and white with columns, backed up onto our more modest blue clapboard, and but for a grove of trees, his lawn crashed into mine.

According to Josh, they’d looked at me through binoculars, seen into my bedroom. Also according to Josh, Mark Miller used his binoculars frequently. I feigned being horrified, but was made giddy by their desire and every time I lowered my blinds that year, I imagined Mark Miller watching me.

My room was invaded by his possibility. The space I’d consecrated with bubble smile letters, Teen Beat posters ripped at the staple line, cats in spread eagle poses, beads and Absolute t-shirts, photos of my cousins and me as babies. All of this became public gallery space. For Mark Miller.

He was handsome, in a Southern Connecticut, lax bro, floppy-haired kind of way. But it was only when I learned he was watching me that the thought of him made me tingle. It was repulsion and desire and I didn’t know what that meant, how to put it in words, so it hung on me like an invisible flannel shirt.

This small fear crept in, too, that someday the boy wouldn’t look through the binoculars at me. There would be another girl, another window. And I wondered at how to stay that girl in that window. It seemed, then, essential to who I was. Who I should be.

All four of the boys in my house today (five, if we’re counting my husband) play a lot of Taylor Swift. “Antihero” crowded every room this spring. There’s double satisfaction in Taylor Swift’s lines “Sometimes I feel like everybody is a sexy baby / and I’m the monster on the hill”. First of all it’s really sweet to think Swift thinks I’m a sexy baby. Secondly, even Swift thinks of herself as the monster on the hill, sometimes.

That same year, when I was 12 and performing in my once private space, a woman walked to the top of the hill in our town’s Mead Park. The woman seemed old to me at the time but now she is both old and young in my imagination. There were boys from my seventh-grade class at baseball practice, hitting grounders. It was after school, sunny with pockets of cold, as Connecticut May’s deliver.

Later, some remembered her walking up the hill, lugging what could’ve been a briefcase, a canteen, something she had to wrestle with, that weighed her down, made her walk look harder than a young woman’s walk up a hill is meant to be.

They all remembered the smoke and then the fire and then the body in the flames, a pyre of its own making. Every one of those boys was brought in for therapy. I remember seeing Josh Santos come out of the middle school counseling office weeping the following Tuesday.

The rest of us were left to process our terror and fantasy of what her kindling might have been through hallway whispers and notes passed in science class, the smell of formaldehyde and latex all around.

The girl in the window, the woman on the hill: they both existed in my preadolescent imagination. I’ve never talked about both of them before, not even to my best friends as we lit candles, pulled out the ouija board, inspected budding breasts, wished ourselves noticed and our enemies unbeautiful. Then, because the words didn’t exist; now, because I haven’t thought about these figures together until this morning, in my classroom, looking at lyrics.

In Human Archipelago, a stunning collaboration of photography by Fazal Sheikh and text by Teju Cole, Cole writes, “I saw myself as I would be if I were to be seen by another. I was for a brief moment no longer myself: I had become a distant vision, as though seen through binoculars, or as though I had become an unexpected character in a story I was telling.”

Sheikh’s photograph accompanying this text is of a boy in a collared shirt and while he looks directly at us, his face is tilted to the right, only his left ear visible. The look my sons give me when they don’t want the exterior world and me intruding on their interior world. His almost-smile betrays nothing, and yet— or maybe because of it— Cole finds himself there, in this boy. How often we are both the voyeur and the observed, how often even our own voyeurs.

I’m thinking now about how being human and in community is axiomatically invasive, seeing ourselves in other people and them in us. And there are so many specter selves: all the former selves, observers of those former selves, and the observed who inhabit our current selves.

We’re, each of us, a Shangri-La.

So much of living is honoring, shushing, ignoring, battling, translating for, offering a glass of milk or a couch to these voices. Even those I don’t want to admit are there, are, ultimately, a reminder.

I look around my classroom, at the table of 17- and 18-year-olds furiously writing, responding to these voices from five or six years ago, a lifetime to them. I’m asking them to write down a version of themselves today and yesterday in the hopes that some of them may return tomorrow to this pen and ink version of themselves. And be reminded, as I am now, that we are large, we contain multitudes2. All of us.

Pseudonyms used throughout

“Do I contradict myself? / Very well then, I contradict myself. / (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” -Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

“My room was invaded by his possibility.” Such an enchanting thought. One that you would feel as a girl but not be able to pinpoint quite that way, with the right words, until you are an adult, let alone an author.

Beautiful. 💯